To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Wound assessment is the initial and follow-up collection of information about a person’s wound, their health history (physical, cognitive, behavioural, spiritual, mental and functional) and environmental factors to understand the likely cause of the wound, plan management approaches and assess the healing process. It is necessary to physically examine the person (for their general health and wellbeing) and the wound to complete a comprehensive wound assessment (Dowsett et al 2015; Phillips et al 2020; Swanson 2014).

Key point

- Efficient wound healing requires optimum management of the person’s general health as well as specific wound management (Dowsett et al 2015; Phillips et al 2020).

Why this is important

Wound assessment provides the foundation for wound care treatment planning, measuring wound healing progress and prompt referral for non-healing or deteriorating wounds (Dowsett et al 2015; Phillips et al 2020). Wound assessment must occur before wound care goals ultimately leading to wound healing can be determined.

In some circumstances (where the person is terminally ill or has untreatable vessel disease), wound healing may not be realistic. In these cases, wound assessment aims to identify wound aetiology, and wound care goals include patient comfort and infection prevention.

Implications for kaumātua*

When completing a wound assessment with kaumātua, it is important to observe the interconnected principles of mana (dignity, prestige, status), tapu (sacred, prohibited, restricted) and noa (neutral, ordinary, unrestricted). See the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information.

Traditionally, mana increases with age (so kaumātua are highly regarded), and as mana increases so does tapu (Mead 2016). All people (and their body fluids) are tapu; the head and sex organs are the most tapu of all. Items that touch the body, especially the head, carry the individual’s tapu.

It is vital to keep tapu and noa separated and balanced to avoid a breach of tapu. Traditionally, breaching tapu incurs the wrath of the atua (gods), which can have a significant spiritual and emotional impact on kaumātua and whānau/family.

In practice, observing these principles means that you:

- avoid damage to tapu and mana by asking for permission to enter personal space (tapu) and to touch the person – touching the head in particular is seen as an intimate act

- keep tapu and noa separate by keeping wound assessment supplies off food or drink surfaces, away from toileting equipment and away from the head and the pillows that the head rests on.

Bear in mind that kaumātua may feel whakamā (shame, embarrassment) about showing an outsider their wound. As a result, they may be reluctant to participate in wound assessment or may under-report their symptoms.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

A wound assessment considers: (World Union of Wound Healing Societies 2020)

- health and environmental factors impacting wound healing, eg, medical conditions, medication, nutrition, hydration and exercise, mental wellbeing, smoking

- wound-specific factors: unrelieved pressure, infection

- wound duration factors:**

-

acute wounds are new with sudden onset and tend to heal in 6 weeks or less; examples include skin tears, surgical incisions

- hard-to-heal wounds (previously called chronic wounds) do not heal in a timely manner; they take longer than 6 weeks to heal or reduce by half; examples include pressure injuries, leg ulcers.

-

**Wound healing times vary: as a pragmatic guide, this document suggests acute wounds heal or reduce by at least 50 percent in 6 weeks and hard-to-heal wounds take longer than 6 weeks to reduce by half or heal.

Tissue type: assess wound bed tissue and percentage of each tissue type

Hypergranulation tissue: is an overgrowth of granulating tissue that sits above the usual level of the skin. It is important to get this tissue checked by GP/NP as it can be malignant. Referral to specialist wound service may be necessary to get treatment advice.

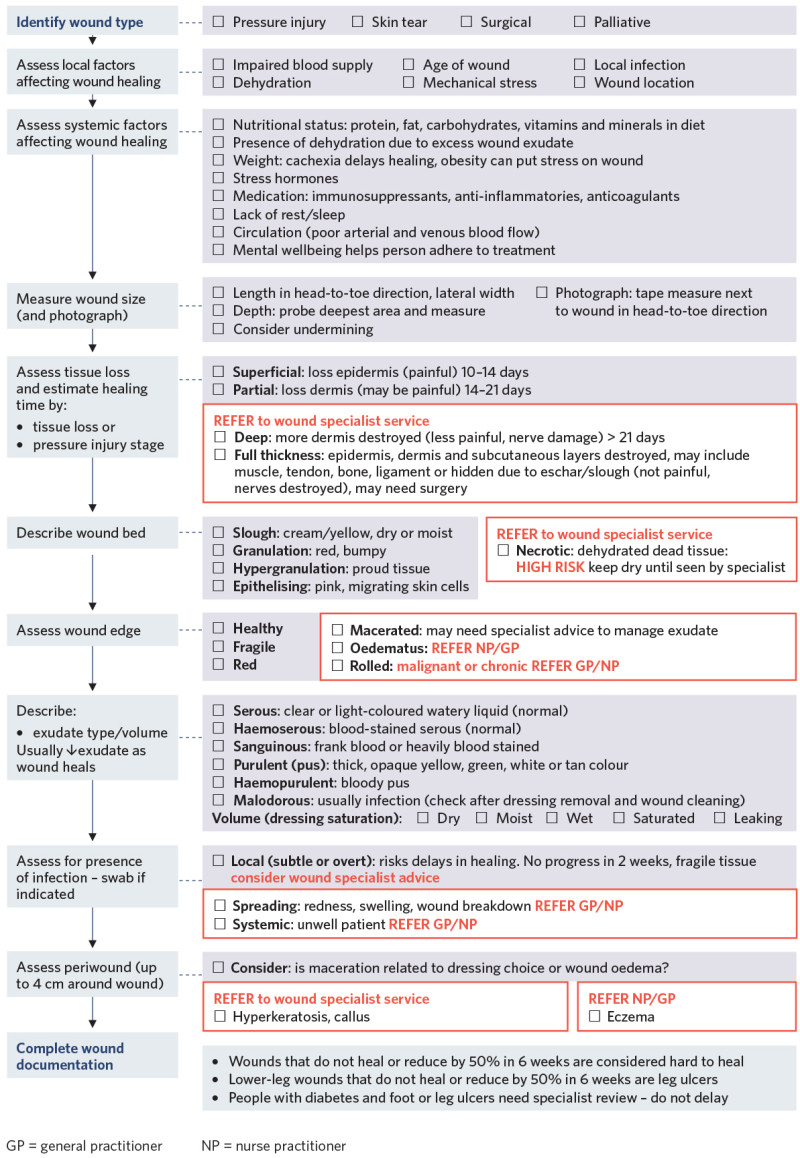

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Infection: assess for infection (IWII 2022) Take a swab if you note symptoms.

Local infection (subtle): delayed healing

- Hypergranulation

- Bleeding, friable granulation tissue

- Epithelial bridging and pocketing

- Increased exudate

- Delayed wound healing

Local infection (overt): wound breakdown

- Redness, warm and swollen tissue

- Purulent discharge

- Wound breakdown or increase size

- New or increased pain

- Malodour

Spreading infection: wound breakdown

- Extending redness, warm and swollen tissue

- Inflammation > 2 cm from wound edge

- Wound breakdown or increased size

- Possible lymph node swelling

Systemic infection: rapid wound breakdown and acutely unwell older person

All signs of infection plus:

- Cellulitis, abscess or pus

- New or increased confusion/delirium

- Lethargy/sleeping more

- Mood or behaviour change

- Pyrexia, fever, chills or hypothermia

- Hypotension, tachycardia

- Swollen lymph nodes (lymphangitis)

- Sepsis

Moisture or exudate

Moist (not wet or dry) wound environments promote wound healing. Assess wound environment and volume of exudate to determine the need to either add or absorb moisture.

Edge of wound: assess wound edge and periwound (up to 4 cm around wound)

Maceration

White, soggy surrounding tissue

- Protect surrounding skin with barrier film or cream

- Review frequency of dressing changes and absorbency of products

Dehydration

Hard, dry surrounding skin

- Rehydrate or moisturise

Undermining

Loss of tissue under wound edges

- Establish depth and stimulate granulation

Rolled edges

Raised, rolled edges around wound

- These can present in older non-healing wounds; consider excluding malignancy

Hyperkeratosis or callus

Hard, dead skin plaques

- Remove and rehydrate

- Seek specialist advice

Eczema (wet or dry)

- If non-responsive to basic moisturisers, review need for steroid therapy with nurse practitioner or general practitioner. May need dermatology review

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Dowsett C, Protz K, Drouard M, et al. 2015. Triangle of wound assessment made easy. Wounds International. URL: woundsinternational.com/made-easy/triangle-of-wound-assessment-made-easy.

International Wound Infection Institute (IWII). 2022. Wound Infection in Clinical Practice. London: Wounds International. URL: woundsinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2023/05/IWII-CD-2022-web.pdf.

Mead HM. 2016. Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values. Wellington: Huia.

Phillips J, Gruys C, Dagger G. 2020. Advisory Document for Wound Bed Preparation in New Zealand: Advancing practice and knowledge in wound management. New Zealand Wound Care Society.

Swanson T. 2014. Assessment. In Swanson T, Asimus M, McGuiness B (eds). Wound Management for the Advanced Practitioner 60–91. IP communications.

World Union of Wound Healing Societies. 2020. Strategies to reduce practice variation in wound assessment and management: The T.I.M.E. Clinical Decision Support Tool. London: Wounds International. URL: www.woundsinternational.com.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.