Urinary tract infections | Te pokenga pūaha mimi (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Care plan

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection in any part of the urinary system, from the urethra and bladder (cystitis) to the kidneys (pyelonephritis). People with a simple (non-complicated) UTI (cystitis) may experience pelvic pain, increased urge to urinate, and pain or burning with urination (dysuria). They can be treated in aged residential care with oral antibiotic therapy (Health Quality & Safety Commission 2022).

Key points

- In aged residential care, up to half of the population have asymptomatic bacteriuria (where bacteria are in the urine but do no harm). It is more common in older women than older men (Givler and Givler 2022).

- A simple UTI can progress to pyelonephritis and sepsis so always consult a nurse practitioner (NP) or general practitioner (GP) as soon as you note symptoms of these more serious conditions. Pyelonephritis symptoms include back pain, nausea, vomiting and fever, confusion, hypothermia and hypotension.

Where possible, treat a UTI with antibiotics when the person has clinical signs and symptoms (following the decision-support flowchart) and lab results are within the specified range.

Why this is important

UTIs cause distress and can lead to more serious conditions. However, unnecessary exposure to antibiotic therapy can lead to antibiotic resistance and adverse medication effects.

Standardising an approach to UTI diagnosis and treatment provides the balance between potential benefits and harms. Te Tāhū Hauora Health Quality & Safety Commission has produced a ‘how to’ guide to support this process (Health Quality & Safety Commission 2022).

Implications for kaumātua*

Kaumātua may experience a sense of whakamā (shame, embarrassment) about their urinary symptoms and so either not disclose or under-report them. They may be a private person who finds discussing symptoms difficult or they may not want to be a bother to others.

It is essential to provide kaumātua and whānau/family with all the information they need to help them understand the approach to managing UTIs in aged residential care. Working with kaumātua and whānau/family may include supporting their use of traditional Māori herbal remedies.

Should kaumātua experience delirium, whānau/family may see this as a disturbance in the resident’s wairua (spirituality) or a breach of their personal tapu (sacredness). It is important to acknowledge this cultural perspective and welcome cultural interventions such as karakia (prayer), pure (cleansing rituals) and whakanoa (ritual that lifts or removes tapu).

See the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Diagnosis – people who can report symptoms

Diagnosis relies on the presence of clinical symptoms and urine laboratory testing (urine microscopy culture and sensitivity testing, MC&S).

1. Clinical symptoms – people without a urinary catheter experiencing situation a, b or c:

a. acute dysuria or

b. fever AND one of the following: acute flank pain or tenderness; suprapubic pain; visible blood in urine; new or increased incontinence, urgency or frequency or

c. two or more of the following: suprapubic pain; visible blood in urine; new or increased incontinence, urgency or frequency.

AND

2. Laboratory testing MC&S – situation a or b:

a. bacterial count > 108 CFU/L with signs and symptoms or

b. bacterial count > 105 CFU/L if specimen collected by intermittent catheterisation.

Diagnosis – people who cannot report symptoms

In situations where residents cannot report their symptoms (eg, those with dementia or communication issues), the nurse will need to observe for changes in cognition, behaviour, function and vital signs to identify deterioration (D’Agata et al 2013). In these circumstances a dipstick urinalysis may be helpful to rule out the diagnosis of UTI (Devillé et al 2004). Unfortunately, a dipstick showing leukocytes and nitrites does not confirm UTI because half of the population ordinarily have bacteria in their urine.

Treatment process

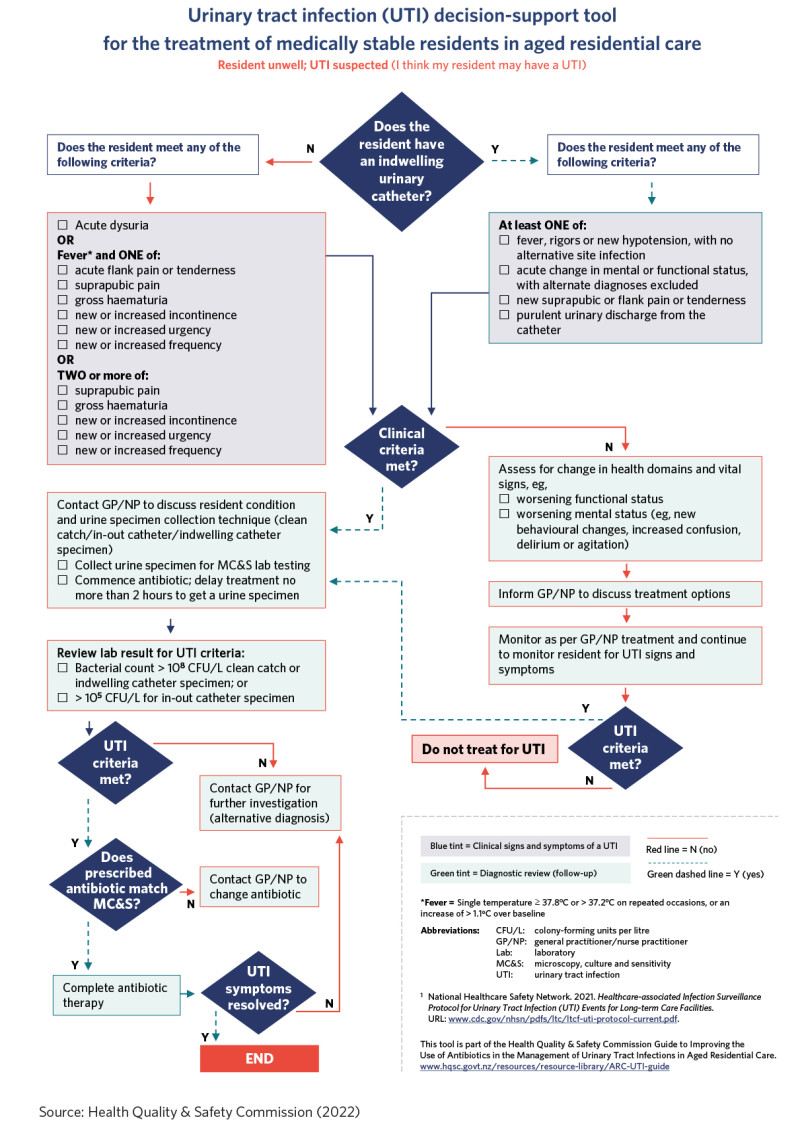

(See decision-support flowchart on the next page for detail.)

1. Identify symptoms.

2. Contact GP/NP for treatment plan.

3. Collect a urine sample for MC&S before administering antibiotic.

a. Clean catch urine or collect through intermittent catheterisation and keep the specimen refrigerated until processed by the laboratory (avoid false results).

b. Do not withhold antibiotic if it is not possible to collect a urine specimen (Gharbi et al 2019).

4. Administer prescribed antibiotic treatment.

5. Review MC&S result.

a. Check antibiotic matches sensitivity reported.

b. Check bacterial count is within the range as described in decision-support flowchart.

6. Contact GP/NP if bacteria are not sensitive to antibiotic, count is not within the range or person deteriorates.

Care plan

Clearly record identified symptoms and treatment plan in resident’s notes. This includes the lab results. Document information related to a resident with suspected UTI and communicate it during handover.

Implement strategies to minimise the risk of UTI for all women living in aged residential care. These include:

- fluid intake of at least 1.5 litres per day (less fluid restricted) (Booth and Agnew 2019); see the Nutrition and hydration | Te taiora me te mitiwai guide

- considering removal of indwelling urinary catheters

- continence assessment and, if necessary, well-fitted products

- hand hygiene (both resident and care provider)

-

avoiding constipation.

Decision support

Urinary tract infection (UTI) decision-support tool for the treatment of medically stable residents in aged residential care

Source: Health Quality & Safety Commission (2022)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Booth J, Agnew R. 2019. Evaluating a hydration intervention (DRInK Up) to prevent urinary tract infection in care home residents: a mixed methods exploratory study. Journal of Frailty, Sarcopenia and Falls 4(2): 36–44. DOI: 10.22540/JFSF-04-036.

D’Agata E, Loeb MB, Mitchell SL. 2013. Challenges in assessing nursing home residents with advanced dementia for suspected urinary tract infections. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 61(1): 62–6. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.12070.

Devillé WLJM, Yzermans JC, van Duijn NP, et al. 2004. The urine dipstick test useful to rule out infections: a meta-analysis of the accuracy. BMC Urology 4: 4. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2490-4-4.

Gharbi M, Drysdale JH, Lishman H, et al. 2019. Antibiotic management of urinary tract infection in elderly patients in primary care and its association with bloodstream infections and all cause mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Education) 364: l525. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.l525.

Givler DN, Givler A. 2022. Asymptomatic bacteriuria. In StatPearls. Tampa, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Health Quality & Safety Commission. 2022. Guide to improving the use of antibiotics in the management of urinary tract infections in aged residential care. Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commission. URL: www.hqsc.govt.nz/resources/resource-library/guide-to-improving-the-use-of-antibiotics-in-the-management-of-urinary-tract-infections-in-aged-residential-care.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.