Urinary incontinence | Te turuturu o te mimi (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Types of urinary incontinence

- Treatment

- Care planning

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Urinary incontinence is the loss of bladder control and the involuntary leakage of urine. Age-related changes to the urinary tract may increase the risk of urinary incontinence. For example, older people may produce more urine at night and have higher residual volumes of urine. Women may experience reduced urethral closure pressure and men increased prostatic obstruction that affects urinary continence.

Key point

- Limited research evidence supports the assessment and treatment of urinary incontinence that older people living with frailty experience (Gibson et al 2021).

Why this is important

Urinary incontinence has the potential to impact on all areas of life. However, the degree of distress associated with this condition varies from person to person.

Implications for kaumātua*

Because some kaumātua may experience a sense of whakamā (shame, embarrassment) over their urinary incontinence, they may either not disclose it or under-report it. They may be a private person who finds discussing incontinence difficult or they may not want to be a bother. See the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information.

It is essential to work with kaumātua and whānau/family to help them engage in prevention, treatment and management options. For example, you need to explain what is known about incontinence and the importance of nutrition and hydration in maintaining usual function. It is also important to support cultural preferences such as traditional Māori herbal remedies. Using familiar, culturally acceptable words when discussing incontinence and continence products (see table below) may also be helpful. Continence New Zealand has additional Māori language resources here.

Kupu (words) to discuss incontinence

| Māori term and pronunciation | English translation |

| Mimi | Urine |

| Turuturu | Leak |

| Māturuturu | Trickle |

| Kope | Pad |

| Wharepaku | Toilet |

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

A comprehensive assessment is recommended because chronic conditions, mobility, cognitive ability, environment and medications all impact on continence, as the Sixth International Consultation on Incontinence explains (Gibson et al 2021).

History of urinary incontinence

- When did incontinence begin?

- What previous treatments has the person received for urinary incontinence and what were the outcomes?

- Detail the characteristics of voiding: frequency, timing, volume, urgency, hesitancy, awareness.

- Consider neurological deficit when a person is not aware that their bladder is leaking or their bladder empties without warning.

- Consider obstruction, eg, prostate enlargement, when the person has trouble starting to pass urine, is straining to pass urine or has poor urine flow.

- Consider residual urine if dribbling occurs after passing urine.

- Consider sphincter strength if person cannot stop the flow of urine.

- What are relieving or aggravating factors, eg, diuretics, tea or coffee?

- What adaptive behaviours does the person use? For example, do they like to stay close to the toilet? Do they limit drinking? Do they go to the toilet ‘just in case’?

- What urinary continence products do they use?

- How does incontinence impact on the person?

Collect detail of toileting situation (collect information over 3 to 5 days)

- Urinary toileting habits: Use tools such as a bladder diary and fluid intake record.

- To understand if constipation is influencing urinary incontinence, collect bowel history (using the Bristol stool chart).

Medical and surgical history

- Hyperglycaemia increases urine production and can risk neuropathic bladder.

- Heart failure increases production of urine at night.

- Stroke can increase urinary retention.

- Dementia or cognitive impairment can make managing continence more difficult.

- Obstetric history influences urinary tract trauma during delivery.

- Chronic constipation worsens urinary incontinence.

- Previous surgery may impact on continence.

Medication

- Consider all medications, recent changes, any ‘as required’ medication, diuretic therapy, sedatives, anticholinergics and psychotropics.

Functional history

- Manual dexterity and mobility influence the time it takes to get to and use the toilet.

- Ability to process the complex task influences toileting response time.

Eating and drinking habits

- Coffee and tea can increase frequency of urination.

- Lack of fluids can result in concentrated urine, which can irritate the bladder.

- Urinary continence is improved by avoiding constipation.

Environmental issues

- Where the person is placed relative to the toilet location influences their toileting response time.

- Access issues include toilet seat height and space in toilet room.

- Consider the colour of the toilet suite for visually or cognitively impaired residents.

Staffing issues

- Consider availability of staff at toileting times and location of older person relative to the location of the staff hub.

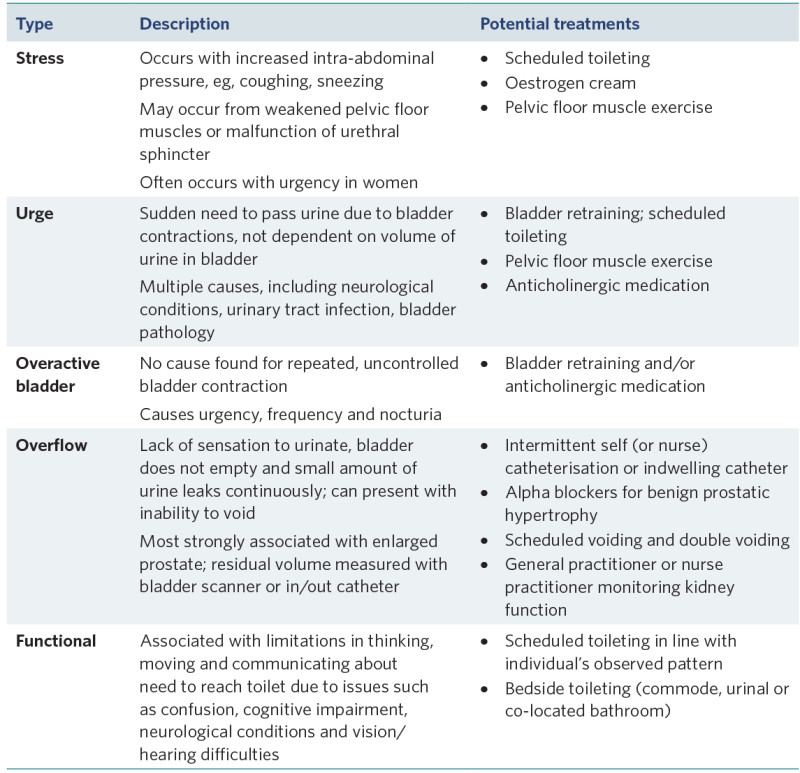

Types of urinary incontinence

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

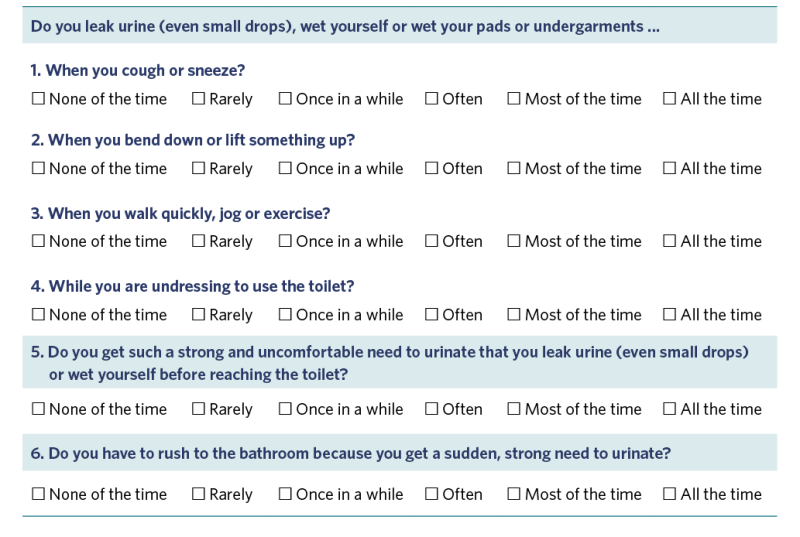

Urinary incontinence assessment questions:

QUID: Questionnaire for female urinary incontinence diagnosis. Questions 1–3 relate to stress incontinence and questions 4–6 to urge incontinence (Bradley et al 2010).

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Further assessment resources

People living in aged residential care are entitled to a continence assessment from a continence nurse specialist. The Continence NZ website hosts a range of tools for residential aged care: www.continence.org.nz/pages/Continence-Information-Adults/18/ (scroll to the bottom of the webpage).

Treatment

Containment

- Urinary continence products are recommended over urinary catheterisation because they have a lower risk of infection. Choose the product based on its match with urine volume.

Physical therapy

- Pelvic floor exercises can be helpful.

- Support general mobility to help the person get to and use the toilet.

Pharmacology

- Antimuscarinic medications (oxybutynin and solifenacin) reduce symptoms of urge incontinence and increase bladder capacity. They may be helpful. However, they also have many adverse effects, including increasing the risk of falls, constipation and urinary retention (New Zealand Formulary nd).

- Local oestrogen therapy (applied to vagina) can help with incontinence related to vaginal atrophy.

- Laxatives can help avoid constipation, a condition that worsens urinary incontinence.

Treat potentially reversible conditions

- Avoid hyper- and hypoglycaemia in diabetes.

- Treat urinary tract infection and inflammation.

- Manage functional limitations.

- Optimise fluid management.

Care planning

Individual assessment is required to understand the impact of incontinence on the person and the capacity to implement interventions.

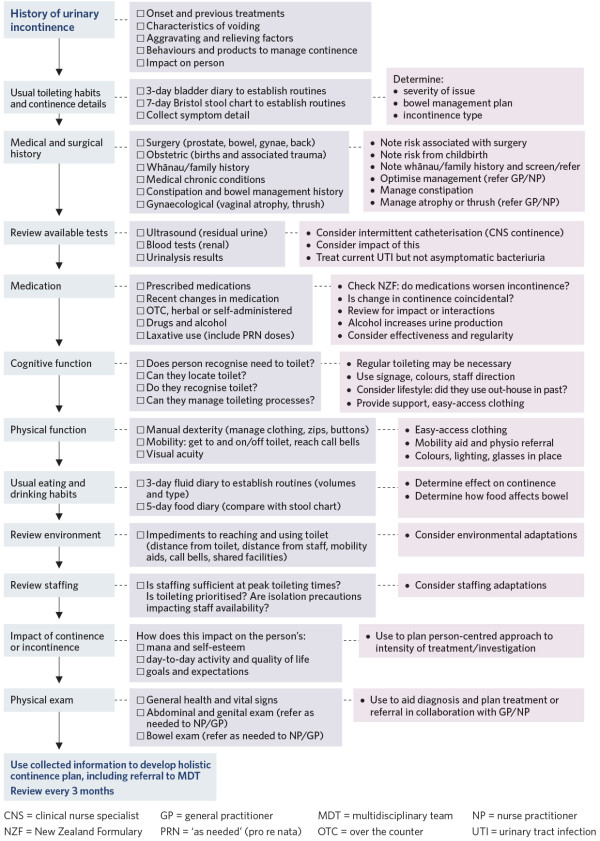

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Bradley CS, Rahn DD, Nygaard IE, et al. 2010. The questionnaire for urinary incontinence diagnosis (QUID): validity and responsiveness to change in women undergoing non- surgical therapies for treatment of stress predominant urinary incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics 29(5): 727–34. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20818.

Gibson W, Johnson T, Kirschner-Hermanns R, et al. 2021. Incontinence in frail elderly persons: Report of the 6th International Consultation on Incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics 40(1): 38–54. DOI: 10.1002/nau.24549.

New Zealand Formulary. nd. Urinary incontinence in women. URL: nzf.org.nz/nzf_4287?searchterm=urinary%20continece.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.