Sexuality and intimacy | Taeratanga me te pā taupiri (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Care planning

- Further resources

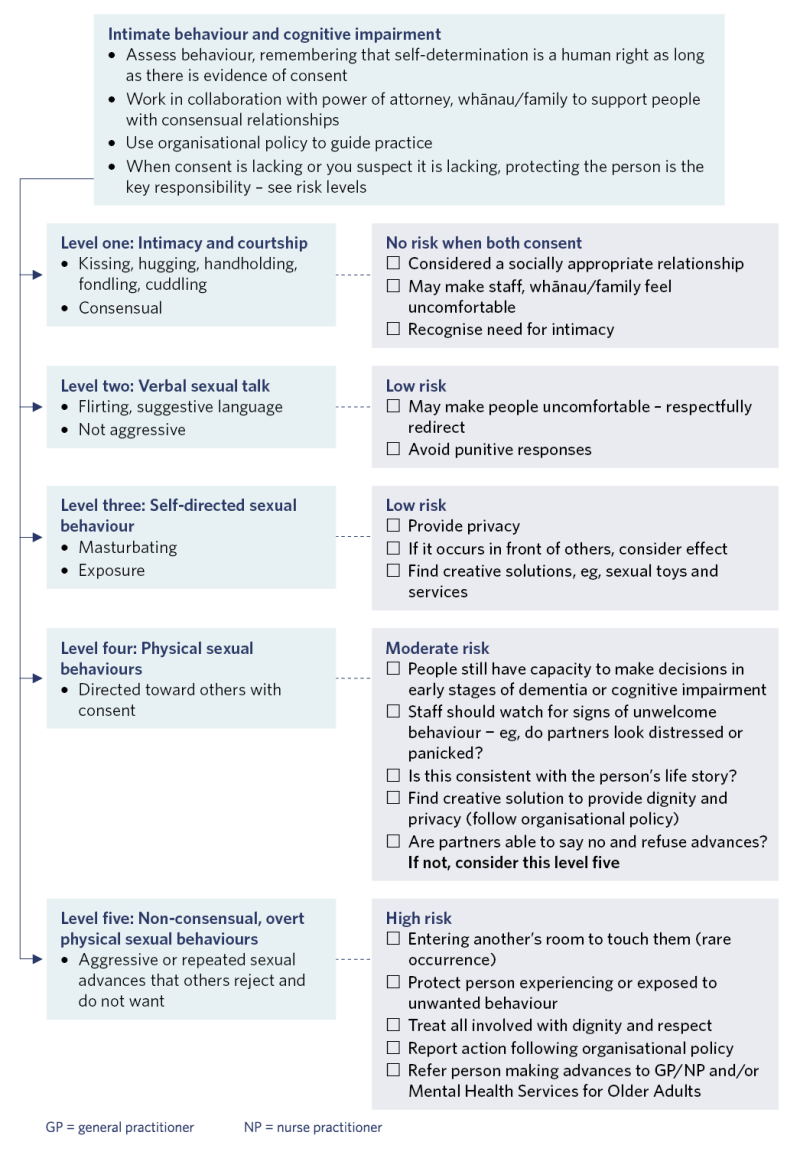

- Decision support adapted from Steele (2007)

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Sexuality is a core aspect of being human. It includes sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. The individual experience or expression of sexuality varies and is influenced by cultural, legal and political situations, religious and spiritual beliefs as well as biological, psychological and social situations (Macleod and McCabe 2020).

Sexual health is defined as ‘a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality’ (McAuliffe et al 2020).

Key points

- The freedom to express sexual identity is a fundamental human right protected by New Zealand law.

- A person’s expression of sexuality and gender identity can be fluid and change throughout life. Sexual and gender diversity is not a new phenomenon. However, it has become more visible as it has become more widely accepted in New Zealand society.

- The need for love and affection continues throughout life (Bauer and Fetherstonhaugh 2016).

Why this is important

Being able to express one’s sexuality brings people psychological and physical comfort irrespective of age (McAuliffe et al 2020). If this basic human need is unrecognised, this can create barriers for an older person in expressing and maintaining sexual health (McAuliffe et al 2020).

A New Zealand study about sexuality in aged residential care (ARC) described loneliness as a key issue when life partners are separated. It also recognised the tension that occurs when the older person’s sexual behaviour does not meet the expectations of their whānau/family (Henrickson et al 2020).

LGBTQI+ is an umbrella term for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and all other people who do not identify as heterosexual. Older people who identify as LGBTQI+ are less likely to have children than their heterosexual counterparts so may lack whānau/family support (Srinivasan et al 2019). These people are also known as the Rainbow community. They may be estranged from whānau/family or continue to conceal their sexuality or gender identity from whānau/family, friends and health staff because they are afraid of discrimination, stigmatisation and isolation.

Implications for kaumātua*

Māori culture traditionally is very accepting of all genders, sexuality and diverse relationships. The inclusion of such topics can be seen in whakairo (carvings) and heard in waiata (songs) and pūrākau (stories). This acceptance may not have been the experience of all kaumātua who identify as takatāpui. Many members of the Rainbow community, both Māori and others, have experienced marginalisation, discrimination and stigma, which can impact on their quality of life (Srinivasan et al 2019).

The term takatāpui embraces all Māori with diverse gender, sexuality and sex characteristics. The term takatāpui can be used in the Māori language to refer to anyone who is gender, sex or sexuality diverse. However, typically only Māori would use this term to self-identify when speaking English. Takatāpui is a uniquely Māori concept that has its own wairua (spirituality) and whakapapa Māori (Māori genealogy).

A Māori view of health is holistic. For this reason, it is important to acknowledge cultural identity as well as gender and sexuality identities as part of the provision of holistic care.

*Kaumātua are individuals and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Sexuality and aged residential care

The Sexuality Assessment Tool was developed to help providers to self-assess their policy and processes related to sexuality in care (Bauer et al 2013).

Keep in mind

Sex work is a legal, regulated profession in New Zealand that can offer a service to people living in ARC. Research suggests use of this service is relatively common in ARC but providers generally do not publicise it due to reputational concerns (Henrickson et al 2022).

Consent and cognitive impairment

Having a diagnosis of cognitive impairment or dementia should not prevent someone from forming new relationships. As long as both parties have the capacity to consent, such relationships should be respected. However, capacity to consent within the sexual and intimacy context needs in-depth exploration and understanding (Hendrickson et al 2020).

When assessing new relationships, consider the following and if in doubt seek expert advice:

- decision-making capacity

- memory and people recognition (is this a case of mistaken identity?)

- verbal and non-verbal expressions of consent

- ability to understand physical and emotional risks involved in intimate relationships

- transgender people with memory loss may experience gender confusion and need particular support to maintain or respond fluidly to gender identity (Baril and Silverman 2019)

- how expectations of whānau/family and health staff may impact on gender and sexually diverse people (possibly increasing the pressure on them to conform to social norms) (Barrett et al 2015).

Approach to sexual disinhibition

Sexual disinhibition can occur in anyone with injury to the brain (trauma, tumour, dementia). Behaviours such as handholding and hugging are considered normal activities; however, where such behaviour is unwanted, it can be damaging to both parties. When assessing whether any intimate behaviour is appropriate, consider the following:

- What form does the behaviour take? (Describe it.)

- In what context does it occur?

- How often does it occur?

- What factors contribute to it?

- Is it really a problem? If so, for whom?

- What is the level of risk? (See the ‘Decision support’ section.)

- Are the people involved able to provide informed consent?

Gender and sexual diversity

Older people belonging to the Rainbow community are likely to be accessing services, even if they do not self-identify openly. So ask them the following:

- How do you identify? (Gender identities are fluid: Marshall et al 2015.)

- What do you like to be called?

- What terms do you use to refer to yourself? (For example, if they use the term ‘gay’, do not use the term ‘homosexual’.)

- Who are the important people in your life?

- Do you have a partner?

- How you like to dress and groom?

- What activities do you like to participate in? (Do not make assumptions about what they enjoy.)

Keep in mind

- Do not confuse a person’s gender diversity and gender expression with sexual orientation.

- Use the person’s preferred pronouns. If you don’t know their preferences, ask.

- Make yourself aware of support services and refer to or invite in expertise.

- Reflect on your own perspective and understanding of the subject matter.

Care planning

Each care plan should identify preferred pronouns, important relationships and gender- affirming activities such as dressing and grooming.

Further resources

Introductory online course on supporting transgender people: genderminorities.com/2021/05/11/supporting-transgender-people-online-course.

Growing up takatāpui (intimate companion of the same sex): takatapui.nz/growing-up-takatapui#resource-intro.

Best practice links in sexuality from Dementia New Zealand: www.nzdementia.org/Best-Practice-Resources/In-residential-care/Sexuality-in-residential-care.

Rainbow Tick New Zealand provides training and organisational development for working with the Rainbow community: www.rainbowtick.nz/#offer.

Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Tarzia L, et al. 2014. Supporting residents’ expression of sexuality: the initial construction of a sexuality assessment tool for residential aged care facilities. BMC Geriatrics 14: 82. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-82.

Decision support adapted from Steele (2007)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Baril A, Silverman M. 2019. Forgotten lives: trans older adults living with dementia at the intersection of cisgenderism, ableism/cogniticism and ageism. Sexualities 25(1–2): 117–31. DOI: 10.1177/1363460719876835.

Barrett C, Crameri P, Lambourne S, et al. 2015. Understanding the experiences and needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans Australians living with dementia, and their partners. Australasian Journal on Ageing 34 (Suppl 2): 34–8. DOI: 10.1111/ajag.12271.

Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D. 2016. Sexuality and People in Residential Aged Care Facilities: A guide for partners and families. Dementia Collaborative Research Centres, La Trobe University and Queensland University of Technology. URL: www.latrobe.edu.au/data/assets/pdf_file/0009/746712/Sexuality-and-people-in-residential-aged-care.pdf.

Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Nay R, et al. 2013. Sexuality Assessment Tool (SexAT) for residential aged care facilities. Melbourne: Australian Centre for Evidence Based Aged Care, La Trobe University. URL: www.dementiaresearch.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/678-dcrc_formatted_sexat_ jan_10_2014.pdf.

Henrickson M, Cook C, Schouten V, et al. 2020. What Counts as Consent? Sexuality and ethical deliberation in residential aged care. Palmerston North: Massey University.

Henrickson M, Cook CM, MacDonald S, et al. 2022. Not in the brochure: porneia and residential aged care. Sexuality Research & Social Policy 19(2): 588–98. DOI: 10.1007/s13178-021-00573-y.

Macleod A, McCabe MP. 2020. Defining sexuality in later life: a systematic review. Australasian Journal on Ageing 39(Suppl 1): 6–15. DOI: 10.1111/ajag.12741.

Marshall J, Cooper M, Rudnick A. 2015. Gender dysphoria and dementia: a case report. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 19(1): 112–7. DOI: 10.1080/19359705.2014.974475.

McAuliffe L, Fetherstonhaugh D, Bauer M. 2020. Sexuality and sexual health: policy in Australian residential aged care. Australasian Journal on Ageing 39(Suppl 1): 59–64. DOI: 10.1111/ajag.12602.

Srinivasan S, Glover J, Tampi RR, et al. 2019. Sexuality and the older adult. Current Psychiatry Reports 21(10): 1–9. DOI: 10.1007/s11920-019-1090-4.

Steele D. 2007. A Best Practice Approach to Intimacy and Sexuality: A guide to practice and resource tools for assessment, response and documentation. Hamilton, Ontario: Lanark, Leeds and Grenville Long-Term Care Working Group. URL: www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/crncc/knowledge/ eventsandpresentations/2012/SexualityPracticeGuidelinesLLGDraft_17.pdf.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.