Responsive and reactive behaviour | Ngā momo whanonga kātoitoi, tauhohe hoki (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Care planning

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Responsive and reactive behaviours are actions, words or gestures of a person living with dementia (PLWD) in response to something negative, frustrating or confusing in their social and physical environment (Alzheimer Society 2013; Scales et al 2018). These behaviours occur because dementia limits a person’s ability to understand their environment, communicate and provide for their own needs. They are best understood as responses to challenges in the physical and social environments rather than symptoms of the disease itself (Cohen-Mansfield et al 2015; Fazio et al 2020).

Responses are wide ranging. At various times they may include agitation, aggression, apathy, withdrawal, anxiety and depression, delusions and/or hallucinations, paranoia, searching (wandering) or restlessness, making unexpected noises, sexual or social disinhibition, loss of emotional control and sleep disturbance (Alzheimer Society 2013; bpacnz 2020; Fazio et al 2020).

Key points

- Thinking of behaviours as communication of unmet need helps carers understand the situation and find solutions (Cohen-Mansfield et al 2015).

- Getting to know the PLWD is the key to working effectively with them and their whānau/family.

- Recommended responses are to have a person-centred culture, identify triggers (antecedents) of behaviour and take a flexible approach to responding to behaviour (Fazio et al 2020).

- Consider medication use carefully. Psychotropic medications can have harmful as well as beneficial effects, and medications for health issues such as pain or depression should be given even when the person cannot communicate about them verbally (bpacnz 2020; Fazio et al 2020; Scales et al 2018).

Why this is important

PLWD can experience severe distress but may have difficulty expressing the reason for distress. Understanding the behavioural expression of distress (seeing the issue from the perspective of the PLWD) is vital to maximising quality of life.

Implications for kaumātua* (Dudley et al 2019)

A Māori world view interprets the behaviour changes in those with mate wareware (dementia) differently from western medicine. The way that kaumātua manifest such behaviour may also differ. For these reasons, you should carefully consider cultural perspectives when assessing and treating kaumātua. For example, anxiety and depression can present with wairua (spiritual) unease, unrest or disturbance, all of which require careful interpretation (bpacnz 2010).

Key aspects of care include:

- providing for the holistic wellbeing of the whole whānau/family, with special consideration for oranga wairua (spiritual wellbeing)

- honouring kaumātua identity

- developing mana-enhancing relationships based on cultural concepts of aroha (compassion, kindness, empathy), manaakitanga (reciprocity, kindness, hospitality), whanaungatanga (relationships, connections) and whakapapa (genealogy).

When planning care, consider treatments that are culturally relevant and appealing such as:

- integrating the use of te reo Māori (which may have been the first language of the kaumātua but they were suppressed from using it as a child)

- participation in cultural activities and events such as waiata (singing), kapa haka (Māori performing arts) and opportunities to manaaki (care for, look after) others.

See the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

It is helpful to use a framework to identify distress and its impact on the person, their whānau/family and others. Many frameworks are available, as follows.

Model of unmet need (Cohen-Mansfield et al 2015)

Distress behaviours are a result of interacting issues. To assess their cause, consider all of these elements:

- lifelong habits and personality

- current physical and mental condition

- environmental issues – physical and psychosocial

- behaviour as a means of fulfilling needs

- behaviour as a means of communicating needs

- behaviour as an outcome of frustration or issue interacting with disinhibition.

Typically, unmet needs are:

- loneliness or need for social interaction

- boredom or sensory deprivation

- need for meaningful activity

- discomfort

- anxiety or need for relaxation

- need for control

- pain.

Impacts on behaviour (James and Jackman 2017)

- What is happening in the environment that impacts on behaviour?

- What is happening for the PLWD that impacts on behaviour?

- What is happening for the care team that impacts on behaviour?

A communication alternative (Fazio et al 2020)

- What is the person expressing?

- What is causing this reaction?

- How can we respond to reduce their distress?

The ABC process (Psychology Tools nd)

- Antecedents: What happened before the event?

- Behaviour: Describe what happened.

- Consequences: What happened next? How did the whānau/family, care team and others respond?

Treatment

It is ‘business as usual’ to minimise distress for everyone in our care. Evidence shows that the following non-pharmacological approaches reduce distress and reactive behaviours in PLWD.

All approaches need to be carefully individualised and evaluated to meet the needs of and take account of the preferences, abilities, habits and roles of the PLWD (including discussing with whānau/family or delegated decision-maker). In health care environments, interventions need to follow provider training and safety protocols.

The following evidence is available on non-pharmacological practices (Scales et al 2018).

Sensory intervention (Scales et al 2018)

- Aromatherapy practices may help to reduce agitation (Scales et al 2018), although research findings are mixed (Livingston et al 2014).

- Massage can reduce non-verbal communication of distress such as agitation, aggression, anxiety, depression and disruptive vocalisations.

- Multisensory stimulation (light, calming sounds, smells and tactile stimuli) can reduce short-term anxiety, agitation, apathy and depression.

Psychosocial (Scales et al 2018)

- Validation therapy focuses empathically on the emotional content of the person’s words or expressions, with the aim of reducing negative and enhancing positive feelings. Validating how the person feels helps to reduce agitation, apathy, irritability and disturbed sleep.

- Reminiscence therapy improves mood without negative effects while focusing on happy memories. Used together with the person’s life story, it can help reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation. (Also be aware of the risk of stimulating unhappy memories.)

- Music therapy can help to reduce anxiety, agitation and apathy in some people (Scales et al 2018). It can be an individualised therapy or used as part of a group leisure activity (while again being aware of the possibility of overstimulation) (Livingston et al 2014).

- Pet therapy can help increase social and verbal interactions, decrease passivity and bring comfort and calm to those who like animals. (Also be aware of allergies or fear of animals.)

- Meaningful activities can help enhance quality of life through engagement, social interaction and opportunities for self-expression and self-determination.

Treating pain in PLWD

Providing adequate pain relief reduces distress in PLWD. However, research shows they are often given less analgesia than people who do not have dementia but have similar chronic conditions (Husebo et al 2011; Nakashima et al 2019).

Communication difficulties can make assessing and managing pain in PLWD difficult so it is important to use a standard pain assessment tool to guide care (Griffioen et al 2019; Paulson et al 2014).

Care planning

Person-centred care (Fazio et al 2018)

Person-centred care (a term first used by Thomas Kitwood) is the approach to care for PLWD that has been most researched and gained the greatest support. The following are key themes of this approach.

- The person living with dementia is more than a diagnosis. Get to know them and support them to uphold their values, beliefs, interests, abilities and personal preferences.

-

See the world from the perspective of the PLWD. Recognise and accept that behaviour is communication. Validating their feelings can help the person connect with their reality.

- Every experience or interaction is an opportunity for meaningful engagement. This should support interests and preferences of PLWD, and allow for their choice (eg, of foods, music, clothes, activities). Remember all PLWD can experience joy, comfort and meaning in life.

- Build and nurture authentic, caring relationships that demonstrate respect and dignity. Focus on the interaction when completing tasks. Supportive relationships are about ‘doing with’ rather than ‘doing for’.

- Create a supportive community that allows for comfort and celebrates success and occasions.

Suggested responses to specific changes in PLWD (bpacnz 2020)

- Agitation: Consider reversible conditions (pain, constipation, infection, acute illness) and environmental factors (boredom or loss of meaningful activity).

- Apathy: Consider engaging in activities such as music, exercise, sensory stimulation.

- Depression: Consider exercise, increased social engagement or cultural connections and medication (see the Depression | Mate pāpōuri guide).

- Anxiety: Identify and manage the cause. Consider environmental factors. Offer emotional support and consider wairua.

- Psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations: Check for: a) reversible causes; b) truth in delusion/hallucination; c) environmental factors. If no modifiable factors are evident, consider referral to specialist services.

- Some culturally specific manifestations could be misinterpreted as delusions or hallucinations, such as where a kaumātua sees or is visited by tīpuna (ancestors). Anyone interpreting such cultural manifestations should only do so from a Māori world view so that the interpretation is accurate and avoids misdiagnosis (bpacnz 2010).

- Wandering: Consider: is this a lifetime habit? Is this searching? Enable safe walking.

- Poor sleep: Assess for and treat underlying conditions or reasons. Minimise night-time noise and light. Establish an evening routine.

- Disinhibition: This can occur due to impaired judgement, poor understanding or misinterpretation of a situation. Support the person rather than scolding them for their actions. Provide the person with privacy and support their dignity at all times.

Other helpful activities

- Give the PLWD access to exercise and physical activity (eg, walking, dancing, exercise classes).

- Help them maintain their own routine. This helps them navigate their day.

- Use the person’s preferred name/term and accept this may change at times.

- If the situation is distressing the PLWD, stop it and give them a break. Consider: is this activity necessary? Are you the right person to help?

Decision support

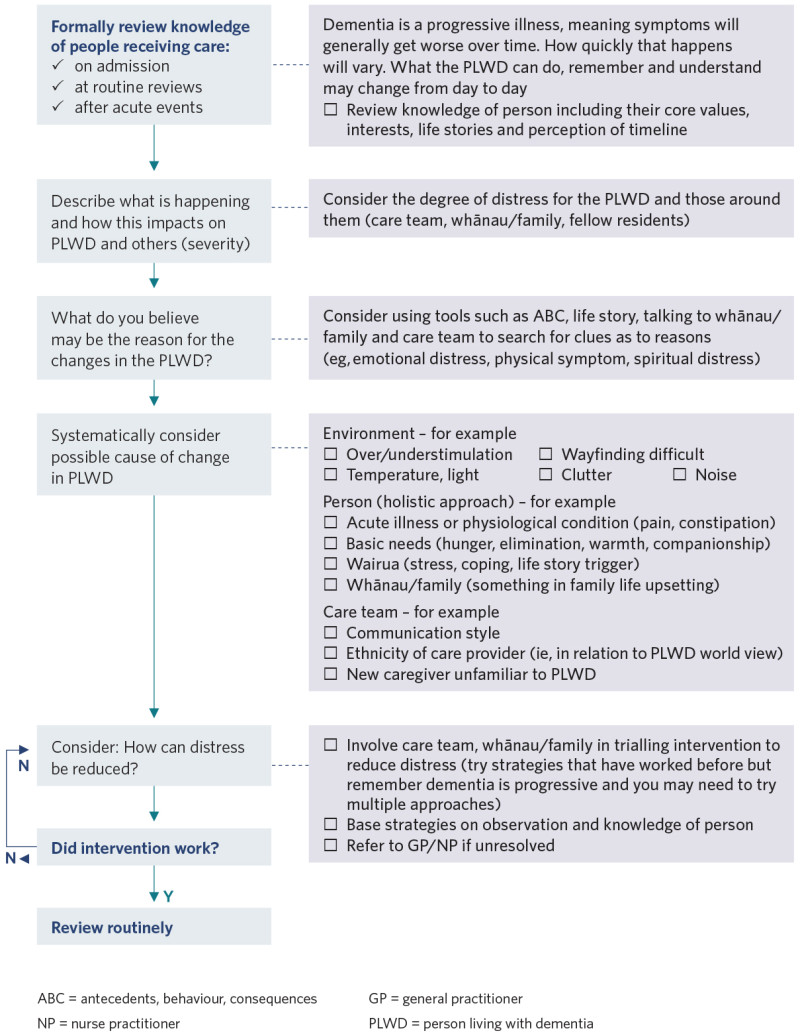

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Achterberg WP, Pieper MJC, van Dalen-Kok AH, et al. 2013. Pain management in patients with dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging 8: 1471–82. DOI: 10.2147/CIA.S36739.

Alzheimer Society. 2013. Shifting Focus: A guide to understanding dementia behaviour. Toronto: Alzheimer Society of Ontario. URL: brainxchange.ca/Public/Files/Behaviour/ShiftingFocusBooklet.aspx.

bpacnz. 2010. Recognising and managing mental health problems in Māori. Best Practice Journal 28: 8–17. URL: bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2010/June/mentalhealth.aspx.

bpacnz. 2020. Managing the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Dunedin: Best Practice Advisory Centre New Zealand.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Dakheel-Ali M, Marx MS, et al. 2015. Which unmet needs contribute to behavior problems in persons with advanced dementia? Psychiatry Research 228(1): 59–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.043.

Dudley M, Menzies O, Elder H, et al. 2019. Mate wareware: understanding ‘dementia’ from a Māori perspective. New Zealand Medical Journal 132(1503): 66–74. URL: journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/mate-wareware-understanding-dementia-from-a-maori-perspective.

Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, et al. 2018. The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist 58(Suppl 1): S10–S19. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnx122.

Fazio S, Zimmerman S, Doyle PJ, et al. 2020. What is really needed to provide effective, person-centered care for behavioral expressions of dementia? Guidance from the Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Provider Roundtable. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 21(11): 1582–6.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.017.

Griffioen C, Husebo BS, Flo E, et al. 2019. Opioid prescription use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Pain Medicine 20(1): 50–7. DOI: 10.1093/pm/pnx268.

Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, et al. 2011. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 343: d4065. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.d4065.

James IA, Jackman L. 2017. Understanding Behaviour in Dementia that Challenges: A guide to assessment and treatment (2nd ed). London and Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley.

Livingston G, Kelly L, Lewis-Holmes E, et al. 2014. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sensory, psychological and behavioural interventions for managing agitation in older adults with dementia. Health Technology Assessment 18(39): 1-226, v-vi. DOI: 10.3310/hta18390.

Nakashima T, Young Y, Hsu WH. 2019. Do nursing home residents with dementia receive pain interventions? American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias 34(3): 193–8. DOI: 10.1177/1533317519840506.

Paulson CM, Monroe T, Mion LC. 2014. Pain assessment in hospitalized older adults with dementia and delirium. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 40(6): 10–5. DOI: 10.3928/00989134-20140428-02.

Psychology Tools. nd. ABC Model. URL: www.psychologytools.com/resource/abc-model.

Scales K, Zimmerman S, Miller SJ. 2018. Evidence-based nonpharmacological practices to address behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The Gerontologist 58(Suppl 1): S88–S102. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnx167.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.