Polypharmacy and deprescribing | Ngā rongoā maha me te whakakore tūtohu (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Polypharmacy is the use of multiple medications. Older people often take many medications to treat conditions, maintain health and prevent future problems. What is important is the effect of the medication rather than the number of medications they use. The aim is always to use medications that benefit the person and eliminate those that may be harmful (Thompson et al 2019).

Deprescribing is the deliberate and systematic act of removing medication and assessing the impact of that change.

Key points

- In aged residential care, regular medication review and associated deprescribing can significantly reduce the number of people with potentially inappropriate medication. It can also reduce the incidents of falling, hospitalisations and overall mortality (Kua et al 2019, 2021).

- As part of the multidisciplinary team, registered nurses make a significant contribution to managing polypharmacy and deprescribing. In particular, they:

- evaluate and report on resident (and whānau/family) understanding of the medication regime, medication preferences, challenges with routes of medication administration, potential adverse drug effects and medication monitoring

- manage the use of ‘as needed’ medications

-

lead the monitoring of residents following deprescribing.

Why this is important

As frailty progresses, physiology, life expectancy and goals of care change. By regularly reviewing medication and then deprescribing where appropriate, health professionals can provide ongoing treatment that best meets the resident’s need.

Implications for kaumātua*

It is important to take a whānau/family-centred approach when changing the medication of a kaumātua. This involves actions such as:

- including whānau/family in conversations

- providing opportunities for whānau/family to share their observations and insights and valuing their input

- allowing adequate time to discuss the matters with all parties involved

- thoroughly discussing and explaining the rationale for medication changes.

When conversations go well, whānau/family may use this opportunity to share important, culturally informed interventions. Supporting these wherever possible is vital to providing holistic care.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Guidelines to reduce potentially harmful medications generally provide lists of medications to review. Managing these lists is often easier with computer support (Monteiro et al 2019; Thompson et al 2019). The following are some guidelines available for potentially inappropriate medication.

- New Zealand criteria have been developed to identify potentially inappropriate polypharmacy in older adults. New Zealand experts recommend a list of 61 medication indicators that should prompt formal medication review (Liu and Harrison 2023).

- From the United Kingdom, the Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy (STOPPFrail version 2) is aimed at older people who have all of the following (Curtin et al 2021):

- limitation with activities of daily living and/or severe chronic disease and/or terminal illness

- severe frailty

- the responsible nurse practitioner or general practitioner would not be surprised if the person died within 1 year.

- Beers Criteria (American Geriatrics Society 2019) have an extensive list of medications and associated risks. Many of the medications listed are not available in New Zealand.

-

An Australian tool is the Medication Appropriateness Tool for Co-morbid Health Conditions in Dementia (MATCH-D) (Page et al 2016).

Treatment

Use a standard tool and nursing observation to identify potentially inappropriate medications and to support deprescribing practice.

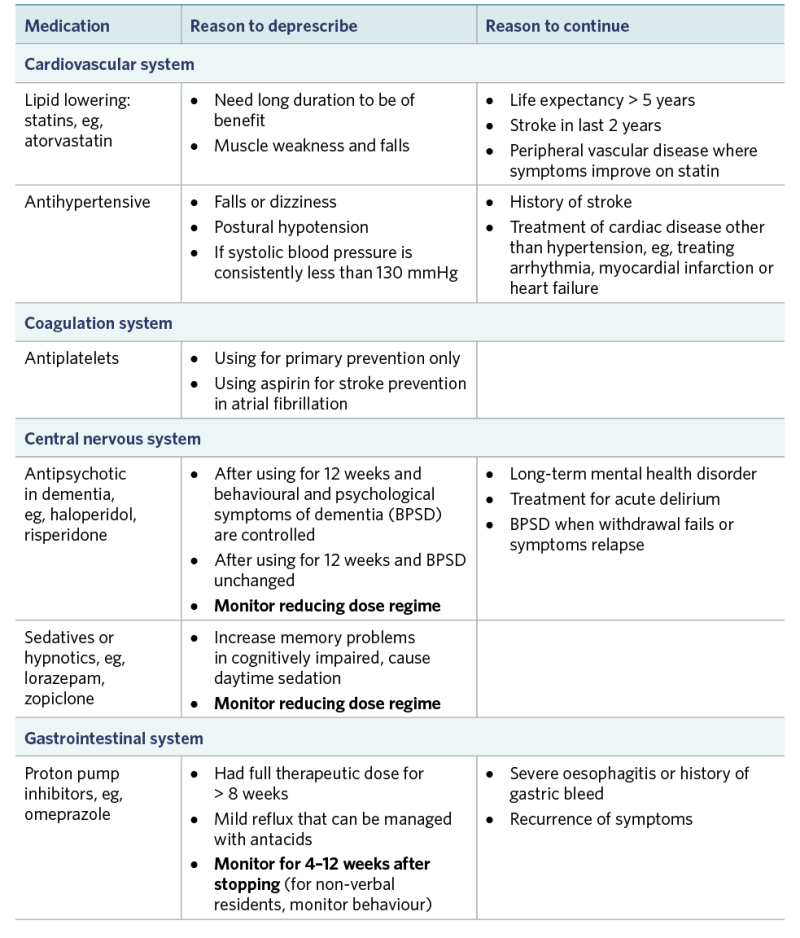

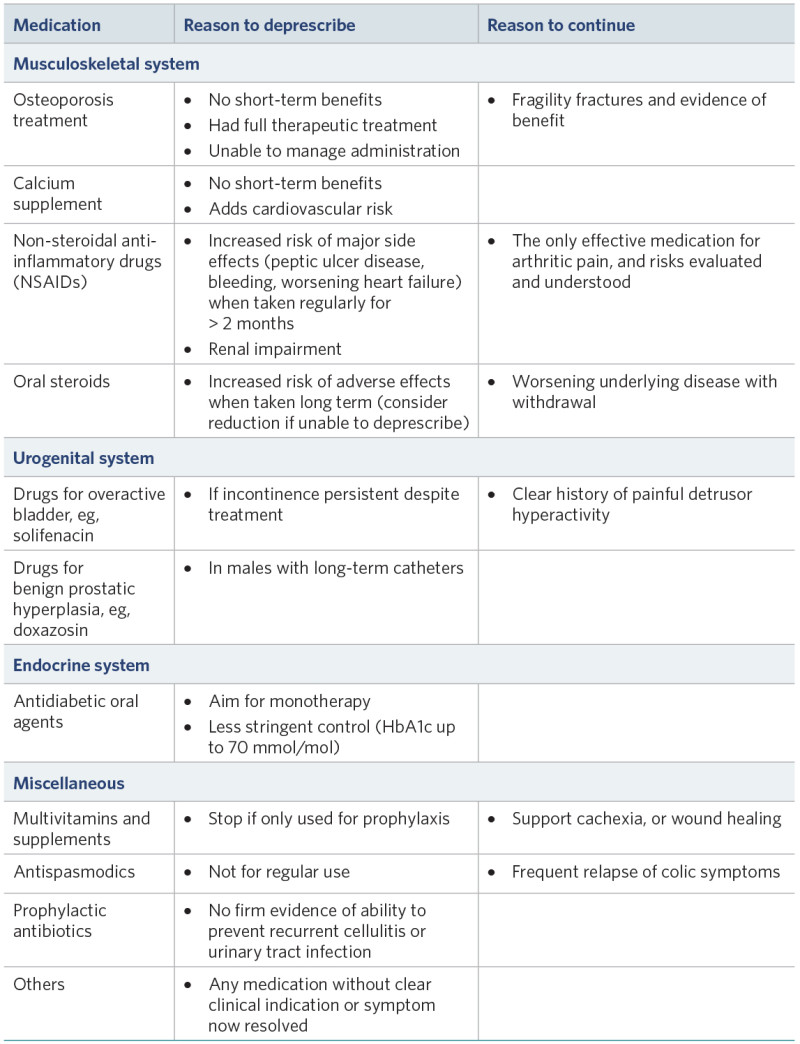

Medications to consider (adapted from STOPPFrail version 2; Frailty Care Guide 2019)

View a higher resolution version of these images in the relevant guide.

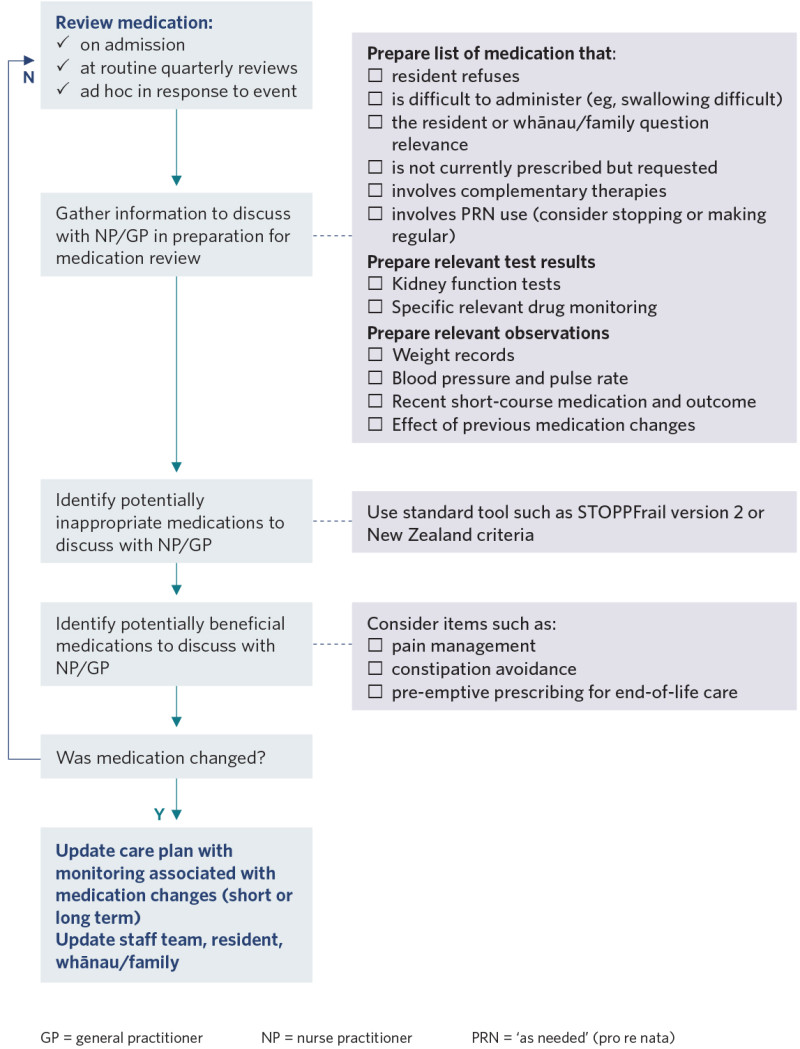

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

American Geriatrics Society. 2019. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 67(4): 674–94. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.15767. (For quick access, go to: www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-work/system-safety/ reducing-harm/medicines/projects/appropriate-prescribing-toolkit/tools-to-guide-which-medicines- should-be-considered-for-deprescribing/#sec1.)

Curtin D, Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. 2021. Deprescribing in older people approaching end-of-life: development and validation of STOPPFrail version 2. Age and Ageing 50(2): 465–71. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afaa159.

Kua C-H, Mak VSL, Huey Lee SW. 2019. Health outcomes of deprescribing interventions among older residents in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 20(3): 362–72.e11. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.10.026.

Kua C-H, Yeo CYY, Tan PC, Char CWT, et al. 2021. Association of deprescribing with reduction in mortality and hospitalization: a pragmatic stepped-wedge cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 22(1): 82–9.e3. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.012.

Liu L, Harrison J. 2023. Development of explicit criteria identifying potentially inappropriate polypharmacy in older adults in New Zealand primary care: a mixed-methods study. Journal of Primary Health Care 15(1): 38–47. DOI: 10.1071/HC22135.

Monteiro L, Maricoto T, Solha I, et al. 2019. Reducing potentially inappropriate prescriptions for older patients using computerized decision support tools: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21(11): e15385. DOI: 10.2196/15385.

Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, et al. 2016. Medication appropriateness tool for comorbid health conditions in dementia (MATCH-D). Internal Medicine Journal 46(10): 1189–97. URL: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5129475/pdf/IMJ-46-1189.pdf.

Thompson W, Lundby C, Graabaek T, et al. 2019. Tools for deprescribing in frail older persons and those with limited life expectancy: a systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 67(1): 172–80. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.15616.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.