To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definitions

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Care planning

- Pain assessment tools

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definitions

As the International Association for the Study of Pain defines it, pain is ‘An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage’ (Raja et al 2020). Further:

- pain is a personal experience influenced by biological, psychological and social factors (such as culture and coping strategies) (Sheikh et al 2021)

- a person’s report of pain experience should be respected. In other words, ‘Pain is what the person says it is’ (Raja et al 2020).

Chronic pain is pain that persists for 3 months or more. It is more common in older people (Robertson 2002; Sheikh et al 2021).

Key points

-

Chronic pain is most common in people living in residential care and those aged 75 years or older (Schofield et al 2022). An Aotearoa New Zealand study reports that approximately 28 percent of people aged 75 years or older experience chronic pain (Dominick et al 2011).

- People can express pain through several different behaviours, not limited to describing it in words. If a person is unable to communicate, that does not rule out the possibility that they are experiencing pain (Raja et al 2020).

- People with cognitive impairment are at greatest risk of undertreatment of pain.

- No one has yet found a definitive approach to pain management (Sheikh et al 2021).

Why this is important

Pain decreases a person’s functional, social and psychological wellbeing (Raja et al 2020) and impacts health-related quality of life. Severe pain is associated with reduced function, poorer physical and mental health and increased risk of mortality (Dominick et al 2011).

Uncontrolled pain is a major cause of delirium (Sampson et al 2020). Moderate to severe pain can impair sleep, increase the risk of falls, put people off eating and hasten frailty progression (Sheikh et al 2021).

Implications for kaumātua*

Culture can impact on the experience and perception of pain as well as the response to pain (Magnusson and Fennell 2011). Understanding this influence is critical when assessing and managing pain.

A Māori view of health is holistic. That means the physical experience of pain impacts on oranga hinengaro (mental health), oranga wairua (spiritual health) and oranga whānau/family (or social health), as well as hauora (wellbeing).

It is important to be able to differentiate between acute and chronic pain, as well as between physical pain and emotional or spiritual pain. When pain is present (chronic) or exacerbated (acute), it is important to involve whānau/family in care and support.

Whānau/family can offer valuable suggestions for culturally informed interventions and help to motivate kaumātua as they are invested in the outcome for their loved one.

Cultural clues may indicate pain has a non-physical source. This is likely to vary from person to person. Again, trusting whānau/family and their input as well as using available cultural advisors will be beneficial in identifying non-physical causes of pain.

It is important to note that some people keep the experience of pain to themselves or minimise the impacts when reporting pain. They may do so because they are very private, do not want to be a burden to others or they experience a sense of whakamā (shame, embarrassment) about discussing such experiences with an outsider (see the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information).

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Health professionals are more likely to identify pain when they are in a ‘pain-vigilant culture’. In this kind of culture, it is common practice to consider the need for pain treatment when a person has a disease known to cause pain, or predispose to pain, as well as when a person experiences and is recovering from trauma (eg, falls, skin tears, pressure injuries) (National Ageing Research Institute Limited 2021).

People may under-report pain for a range of different reasons. These include but are not limited to: a) believing pain is a ‘natural’ part of ageing, b) fear of becoming addicted to pain medication, c) fear of the underlying cause of pain and d) cultural norms that reduce expressions of pain (National Ageing Research Institute Limited 2021).

- People with cognitive impairment may be unable to accurately report pain in words. In these cases, look for non-verbal indicators of pain. It can be helpful to use a standard assessment tool, such as the PAINAD (Warden et al 2003) or Abbey Pain Scale (National Ageing Research Institute Limited 2021), in addition to asking the person about their pain.

- When people can report pain, exploring their experience using a tool such as OLDCARTS-ICE is the essential first step in managing the pain.

- You can use a tool such as the Brief Pain Inventory to guide people in self-reporting the intensity and impact of pain.

- Listen to the person’s concerns about pain (what pain means to them).

- Engage whānau/family in identifying and managing pain. (They may see subtle signs that health professionals do not notice.)

- New pain is a significant event. The general practitioner (GP) or nurse practitioner (NP) should evaluate it fully.

Treatment

Pain is more often undertreated than overtreated in older people. After a thorough pain assessment, a multimodal approach to pain management is recommended (Sheikh et al 2021). While non-pharmacological treatments are the first step, health professionals should not withhold effective pharmacological treatments (Schofield et al 2002). However, even with the best treatment, for some people it may only be possible to achieve a 30 percent reduction in symptoms (Sheikh et al 2021).

Non-pharmacological treatment

- Offer music and spiritual support.

- Keep the person moving (which may involve anything from repositioning in bed to walking).

- Support the person to eat well. Maintaining strength and eating favourite foods improves mood.

- Support sleep.

- Provide complementary therapies, such as massage, aromatherapy, soaking in a warm bath and/or pet therapy.

- Safely apply heat (refer to your facility’s policy).

- Safely apply cold (refer to your facility’s policy).

- Use culturally informed interventions (eg, mirimiri, reiki, karakia).

Pharmacology

The nurse has an important role in pain medication management through:

- administering and monitoring analgesics for effectiveness

- slowly increasing analgesics after they are started at a low dose (to effect)

- taking care to properly space the timing of analgesia for maximum effect

- reviewing the use of as needed (PRN) medications and discussing with the GP/NP if prescriptions need changing

- proactively using available PRN medications in response to pain.

Medications

- Paracetamol is indicated for musculoskeletal pain, osteoarthritis of the hip and knee and lower back pain. For low-weight (< 50 kg) older people with frailty, one study recommends a maximum 24-hour dose of 3 g (Sheikh et al 2021). However, other authors report that no good-quality evidence is available to either support or refute this lower standard maximum dose (Caparrotta et al 2018).

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are generally not recommended for older people. If used, this should be for short courses only as they can cause harm (particularly gastrointestinal injury and increased renal impairment) and result in hospitalisation (Sheikh et al 2021). The prescriber considers the harm–benefit balance, and the nursing team needs to assess for evidence of harm (eg, abdominal pain, fluid retention or bleeding). These medications are generally not advised in heart failure, gastrointestinal disease and renal disease.

Note: Studies indicate that topical NSAIDs are safer than oral ones (Schofield et al 2022).

-

Opioids are indicated for moderate to severe pain. They are generally not indicated for chronic pain. A GP or NP may issue these medications based on individual assessment. However, they are best used for acute pain, short-course therapy or end-of-life care.

Monitoring includes evaluation of renal and liver function and adverse effects:

- Strong opioids (morphine, oxycodone): Assess for sedation, respiratory depression, muscle twitching and constipation.

- Weak opioids (codeine): Assess for constipation.

- Atypical opioids (tramadol): Assess for delirium.

- Transdermal opioids (fentanyl): These take 24 hours to reach maximum effect and 24 hours to clear the system if stopped. Assess for sedation and significant respiratory depression when starting, increasing or stopping patches. A monitoring period of at least 24 hours is required (Schofield et al 2022). Patches are not recommended for people who have never had opioids before.

- Adjuvant analgesics are indicated for neuropathic pain (Schofield et al 2022; Sheikh et al 2021). They include:

- tricyclic antidepressants, but assess for cardiac side effects

- anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin)

- cannabidiol, although the current recommendation is to avoid it due to central nervous system side effects (Sheikh et al 2021).

Care planning

A patient-centred approach to care planning is recommended. This involves setting goals for pain management and using the multidisciplinary team to address all aspects of care that potentially may impact on pain.

Consider all possible impacts, including physical, psychological, whānau/family and spiritual impacts. Include any culturally informed triggers or interventions that whānau/family or cultural advisors have identified in the care plan.

Pain assessment tools

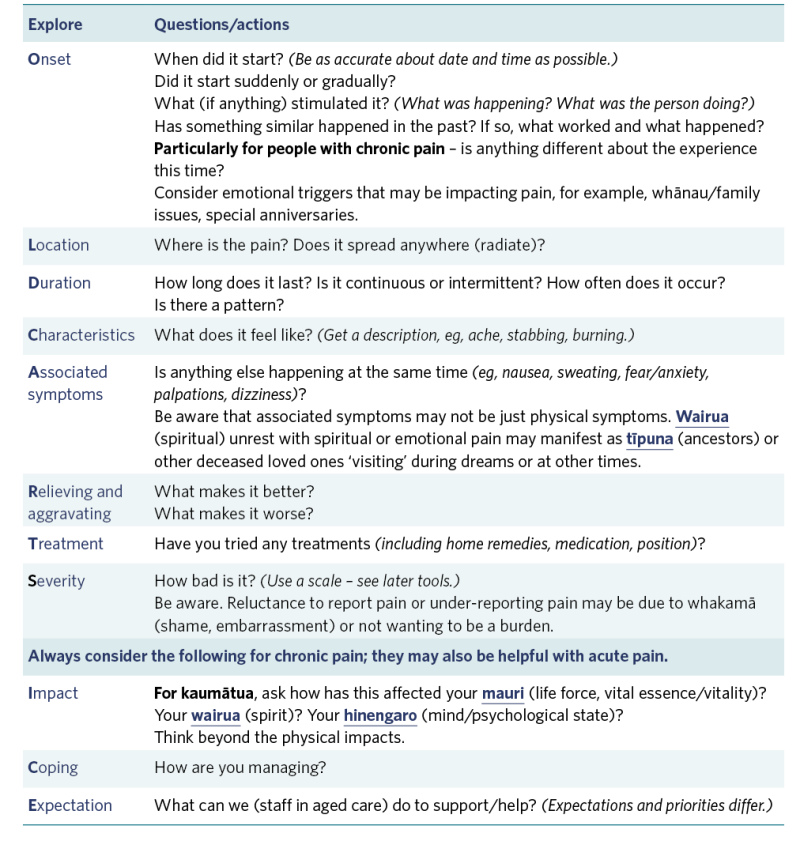

Pain history collection: OLDCARTS-ICE

While primarily designed as a way to interview patients, OLDCARTS-ICE is also a useful tool for exploring the symptoms and expectations from the perspective of whānau/family or designated decision-makers.

OLDCARTS-ICE

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

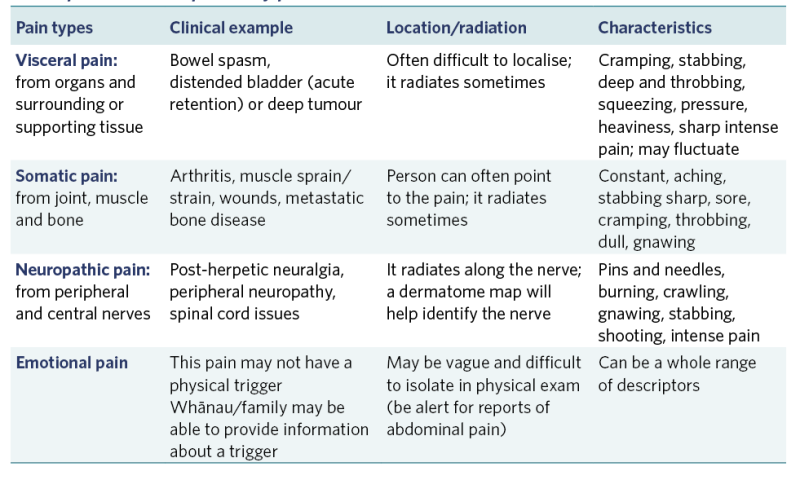

Descriptions that help identify pain

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Brief pain inventory

A tool for people to self-report their pain. Examples are freely searchable: www.apsoc.org.au/PDF/Publications/APS_Pain-in-RACF-2_M-RVBPI.pdf (PDF, 112 KB).

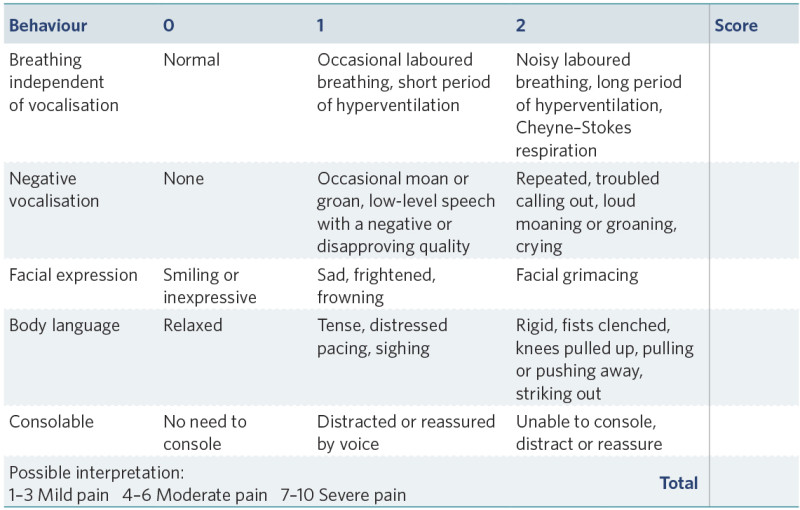

Validated pain assessment tools

Use when people have cognitive impairment or communication difficulties.

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale: PAINAD (Warden et al 2003)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

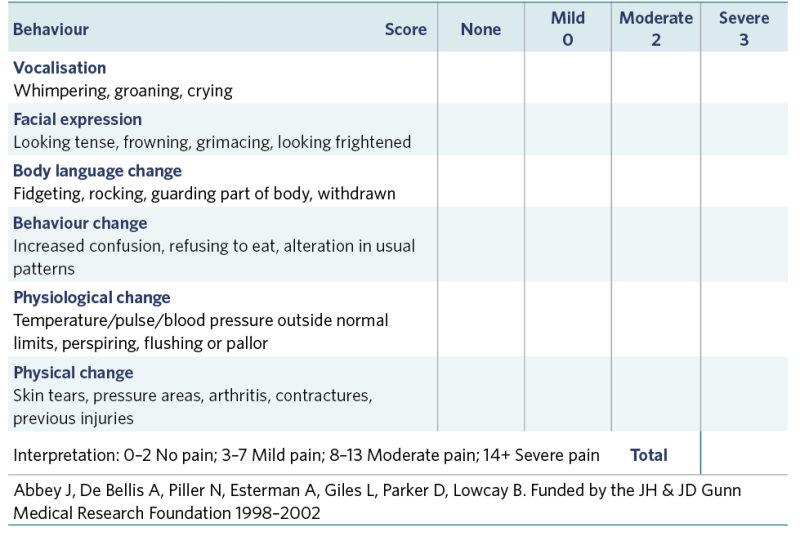

Abbey Pain Scale (National Aging Research Institute Limited 2021)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Abbey J, De Bellis A, Piller N, Esterman A, Giles L, Parker D, Lowcay B. Funded by the JH & JD Gunn Medical Research Foundation 1998–2002

Electronic (app-based) tools such as ‘PainChek’ artificial intelligence facial analysis may also be useful. Some providers are integrating it into their care management systems (see www.painchek.com/use-cases/residential-aged-care).

References | Ngā tohutoro

Caparrotta TM, Antoine DJ, Dear JW. 2018. Are some people at increased risk of paracetamol-induced liver injury? A critical review of the literature. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 74(2): 147–60.

Dominick C, Blyth F, Nicholas M. 2011. Patterns of chronic pain in the New Zealand population. New Zealand Medical Journal 124(1337): 63–76.

Magnusson JE, Fennell JA. 2011. Understanding the role of culture in pain: Māori practitioner perspectives relating to the experience of pain. New Zealand Medical Journal 124(1328): 1–143.

National Ageing Research Institute Limited. 2021. Pain Management Guide (PMG) Toolkit for Aged Care (2nd edition). URL: www.nari.net.au/pmg-toolkit-for-aged-care-2nd-edition.

Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, et al. 2020. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 161(9): 1976–82.

Robertson SA. 2002. What is pain? Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association 221(2): 202–5.

Sampson EL, West E, Fischer T. 2020. Pain and delirium: mechanisms, assessment, and management. European Geriatric Medicine 11(1): 45–52.

Schofield P, Dunham M, Martin D, et al. 2022. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on the management of pain in older people: a summary report. British Journal of Pain 16(1): 6–13.

Sheikh F, Brandt N, Vinh D, et al. 2021. Management of chronic pain in nursing homes: navigating challenges to improve person-centered care. Journal of American Medical Directors Association 22(6): 1199–205.

Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer L. 2003. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. Journal of American Medical Directors Association 4(1): 9–15.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.