To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Care planning

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Frailty is an age-related, progressive (Pazan et al 2021) geriatric syndrome with many dimensions and causes (physical, cognitive and social). It is characterised by reduced strength, endurance and physiological and psycho-social function. Frailty increases an individual’s vulnerability to poor health outcomes (Dent et al 2017; Morley et al 2013; Vermeiren et al 2016).

Key points

-

The three broad approaches to defining frailty are: (a) physical frailty (Fried et al 2001); (b) deficit accumulation model (Rockwood and Mitnitski 2007); and (c) combination model: frailty as an effect of physical, cognitive and social elements (Rolfson 2022).

- Frailty is age related. It is most common in people aged 85 years and older.

- Māori experience frailty at a younger age than other ethnic groups (bpacnz 2018).

Why this is important

Frailty is the most common underlying cause of illness and death among people living in aged residential care (Amblàs-Novellas et al 2016). It is a progressive syndrome that can be slowed but not stopped. Older people with severe frailty are less likely to recover from acute illness than people of the same age without frailty (Murray et al 2005; Pulok et al 2020; Stow et al 2018). Frailty scales can support conversations with older people and their whānau/family about goals of care.

Remember, older people are assumed competent. It is only when a formal capacity assessment establishes they lack ‘capacity’ that it is possible to activate an enduring power of attorney (EPoA) for personal care and welfare. When the EPoA is activated, the attorney has the legal responsibility to make sound decisions on behalf of the older person.

Key points

- Relatively small stressors (such as a change in medication or an infection) can result in

severe clinical deterioration in older people with frailty (Clegg et al 2013). - Acute deterioration may present as acute confusion, extreme weakness or fatigue and change the person’s behaviour or function (Clegg et al 2013) before vital signs change.

Implications for kaumātua

Te ao Māori (Māori world view) has a perspective of ageing based on a strength rather than a deficit model, and traditionally kaumātua* have a lot of mana (dignity, respect, status). This means that the focus of care should be on who the person is and what they are still able to do.

Frailty is complex. It is important to note that kaumātua will differ in their experience of symptoms, even when those symptoms are the same. Individuals will also differ in the challenges they face and in their needs. You should tailor care specifically to the needs of the individual.

A Māori view of frailty is that it is a ‘multidimensional experience encompassing physical and functional, social and whānau/family, psychological, environmental and macro-level factors’. Further, ‘the experience of frailty is a dynamic balance between challenges/deficits and strengths/resources’ (Gee et al 2021).

Factors that have a positive or balancing effect on kaumātua holistically (Gee et al 2021) include:

- feeling engaged and connected to people (whānau/family support, social networks, bonds with whānau/family including mokopuna [grandchildren])

- feeling useful and having a purpose (manaaki [looking after/giving support to] others, having a role as kaumātua of being central to whānau/family)

- having a sense of autonomy, mana and confidence (support people can recognise and strengthen these self-concepts or erode them)

- cultural identity (eg, practising tikanga and visiting marae can help them feel uplifted)

- oranga wairua (spiritual wellbeing).

Consider that pride may stop some kaumātua from accepting help or using aids. It is important to offer help proactively as kaumātua may be whakamā (ashamed/embarrassed) to ask for help due to a traditional view that this is rude or shameful, and because they do not want to bother anyone else.

Holistic care also includes equipping whānau/family with all of the information, knowledge and resources that will best support their ongoing involvement in the care of their loved ones.

For more information about any of the above, see the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

International and Asia-Pacific (Dent et al 2017) frailty guidelines recommend assessing a person with a standard, recognised frailty tool.

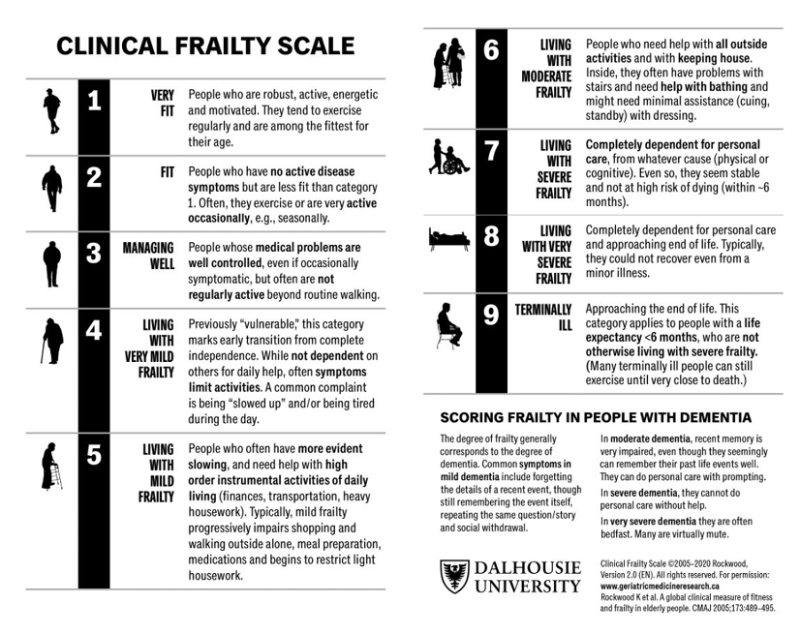

- The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (Rockwood and Theou 2020) uses descriptions and images to categorise frailty stages (Oviedo-Briones et al 2021). Each category is related to an increase in the risk of death over the medium term (Pulok et al 2020). The CFS takes less than 30 seconds to complete (Oviedo-Briones et al 2021). Its clear, picture-based approach to frailty stages is helpful when discussing goals of care with residents and whānau/family.

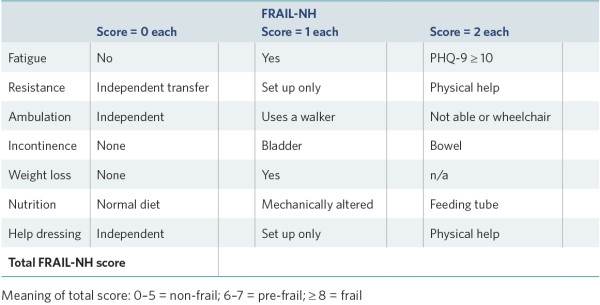

- The FRAIL-NH tool is aimed at health professionals. It is straightforward to use, and over 20 countries have used it. Research shows it is good at predicting adverse outcomes in people living in aged residential care (Liau et al 2021).

Frailty assessment tools

FRAIL-NH (Kaehr et al 2015; Oviedo-Briones et al 2021)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Source: Rockwood and Theou (2020); Rockwood et al (2005)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Treatment

Evidence shows a limited number of interventions slow the progression of frailty. Effective interventions are physical activity and strength training, nutritional supplements, weight monitoring, addressing polypharmacy, vitamin D supplements for those with deficiency, screening for causes of fatigue and optimising the management of chronic conditions (Dent et al 2017, 2019).

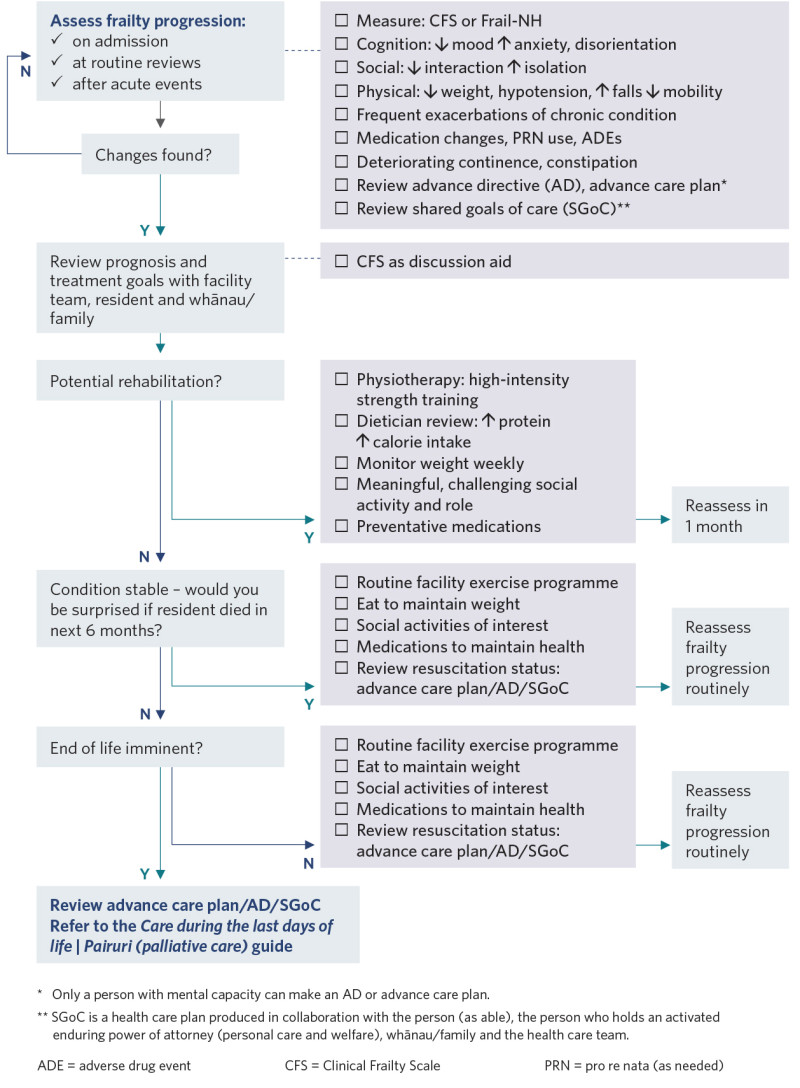

Care planning

Because frailty is multidimensional, a comprehensive care plan is needed to address it. Consider all the care guides relevant to the individual. Pay particular attention to physical activity, nutrition, medication and chronic conditions (Dent et al 2017, 2019). Care planning includes: routinely reassessing frailty; supporting cognition, social engagement, physical function and chronic conditions; remaining alert for acute deterioration; and planning for future care (Pulok et al 2020)

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Amblàs-Novellas J, Murray SA, Espaulella J, et al. 2016. Identifying patients with advanced chronic conditions for a progressive palliative care approach: a cross-sectional study of prognostic indicators related to end-of-life trajectories. BMJ Open 6(9): e012340. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012340.

bpacnz. 2018. Frailty in older people: a discussion. URL: bpac.org.nz/2018/frailty.aspx.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. 2013. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381(9868): 752–62. DOI: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(12)62167-9.

Dent E, Lien C, Lim WS, et al. 2017. The Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines for the management of frailty. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 18(7): 564–75. DOI: 10.1016/j. jamda.2017.04.018.

Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. 2019. Physical frailty: ICFSR international clinical practice guidelines for identification and management. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 23(9): 771–87. DOI: 10.1007/s12603-019-1273-z.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. 2001. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 56(3): M146-56. DOI: 10.1093/ gerona/56.3.m146.

Gee S, Bullmore I, Cheung G, et al. 2021. It’s about who they are and what they can do: Māori perspectives on frailty in later life. New Zealand Medical Journal 134(1535): 17–24. URL: www.researchgate.net/publication/351762684_It%27s_about_who_they_are_and_what_they_can_do_Maori_perspectives_on_ frailty_in_later_life.

Kaehr E, Visvanathan R, Malmstrom TK, et al. 2015. Frailty in nursing homes: the FRAIL-NH Scale. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 16(2): 87–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.12.002.

Liau SJ, Lalic S, Visvanathan R, et al. 2021. The FRAIL-NH Scale: systematic review of the use, validity and adaptations for frailty screening in nursing homes. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 25(10): 1205–16. DOI: 10.1007/s12603-021-1694-3.

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. 2005. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 330(7498): 1007–11. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007.

Oviedo-Briones M, Laso ÁR, Carnicero JA, et al. 2021. A comparison of frailty assessment instruments in different clinical and social care settings: the frailtools project. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 22(3): 607.e7–607.e12. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.024.

Pazan F, Petrovic M, Cherubini A, et al. 2021. Current evidence on the impact of medication optimization or pharmacological interventions on frailty or aspects of frailty: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 77(1): 1–12. DOI: 10.1007/s00228-020-02951-8.

Pulok MH, Theou O, van der Valk AM, et al. 2020. The role of illness acuity on the association between frailty and mortality in emergency department patients referred to internal medicine. Age and Ageing 49(6): 1071–9. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afaa089.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. 2007. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 62(7): 722–7. DOI: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722.

Rockwood K, Theou O. 2020. Using the clinical frailty scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Canadian Geriatrics Journal 23(3): 210–5. DOI: 10.5770/cgj.23.463.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. 2005. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Canadian Medical Association Journal 173(5): 489–95. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.050051.

Rolfson D. 2022. Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS). URL: edmontonfrailscale.org/.

Stow D, Matthews FE, Hanratty B. 2018. Frailty trajectories to identify end of life: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Medicine 16(1): 171. DOI: 10.1186/s12916-018-1148-x.

Vermeiren S, Vella-Azzopardi R, Beckwée D, et al. 2016. Frailty and the prediction of negative health outcomes: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 17(12): 1163.e1–1163.e17. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.010.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.