To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Hypoglycaemia decision support

- Hyperglycaemia decision support

- Treatment

- Care planning: monitoring

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a term used to describe a group of conditions that result in hyperglycaemia (high blood glucose) from either a lack of insulin production or insensitivity to insulin that is produced (New Zealand Formulary 2022a).

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) occurs in over 90 percent of DM cases. It involves both reduced insulin production and insulin insensitivity. People with T2DM are treated with a range of hyperglycaemic tablets and/or insulin.

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) occurs where a loss of beta-cells in the pancreas results in a lack of insulin production. People with T1DM need insulin to survive.

Why this is important

An estimated 300,000 people in New Zealand have DM. Pacific peoples have the highest rate, followed by Indian and Māori populations. New Zealand Europeans have the lowest rate of DM (Te Whatu Ora 2023). Long-term diabetes causes a wide range of complications, including loss of vision, kidney disease, heart disease, chronic wounds and amputations. In the short term, extremes of blood glucose levels (hypo and hyperglycaemia) result in significant illness and mortality.

Implications for kaumātua*

Compared with New Zealand Europeans, Māori are two to four times more likely to be diagnosed with T2DM and to experience diabetes-related complications. They also have higher rates of mortality associated with diabetes (Mullane et al 2022; Yu et al 2021).

Māori have a holistic view of health and wellbeing. As diabetes affects every aspect of life, it is important to consider care from this perspective, rather than focusing solely on the disease of diabetes. A holistic approach takes account of the person’s spiritual and emotional wellbeing, and includes their whānau/family. Research shows that providing care in which people and whānau/family feel culturally safe, taking a whānau/family-centred approach and using Māori principles, approaches and perspectives can all have a positive impact on the health of kaumātua (Tane et al 2021).

See the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information.

The following are two key aspects to consider in your approach to care.

- The sharing of kai (food) is closely connected to manaakitanga (hospitality, reciprocity) and whanaungatanga (connectedness), which are central constructs in te ao Māori (Māori world view). For this reason, food and nutrition have spiritual and social significance, beyond physical sustenance.

- Some kaumātua and whānau/family may see symptoms associated with hypoglycaemia as wairua (spiritual) unrest or disturbance. Where they do, supporting holistic interventions is essential. (See the Delirium | Mate kuawa guide for more information.)

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

The aim of day-to-day assessment is to keep older people safe. Its main focus is on managing blood glucose levels and diabetes medication and responding to sick days.

Blood glucose level (BGL) targets

Frail older people are at greater risk from hypoglycaemia (which can cause falls, cognitive decline, dementia, myocardial infarction, stroke and death) than the longer-term health outcomes of diabetes. Because of this, treatment focuses more on quality of life than on risk of future problems and so BGL targets are less tightly controlled.

Target HbA1c ranges in older people (bpacnz 2019):

- older people (not frail): HbA1c of 58–64 mmol/mol

- older people with frailty: HbA1c up to 70 mmol/mol.

Where an older person with frailty exceeds the target of HbA1c up to 70 mmol/mol, they have a greater chance of glycosuria, dehydration, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar syndrome, candidiasis, urinary tract infections and poor wound healing.

BGL monitoring frequency in stable disease

The general recommendation is to measure HbA1c 6 monthly. (Discuss individuals with their general practitioner [GP] or nurse practitioner [NP].) More frequent monitoring is recommended if HbA1c is below 58 or above 70.

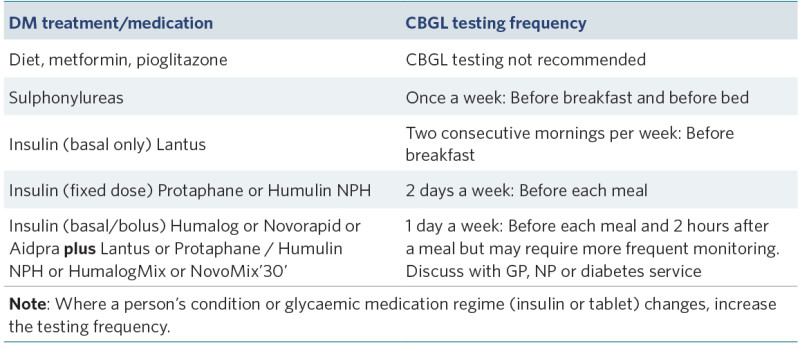

Suggested capillary blood glucose level (CBGL) testing regimes (Health Hawke's Bay 2023)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

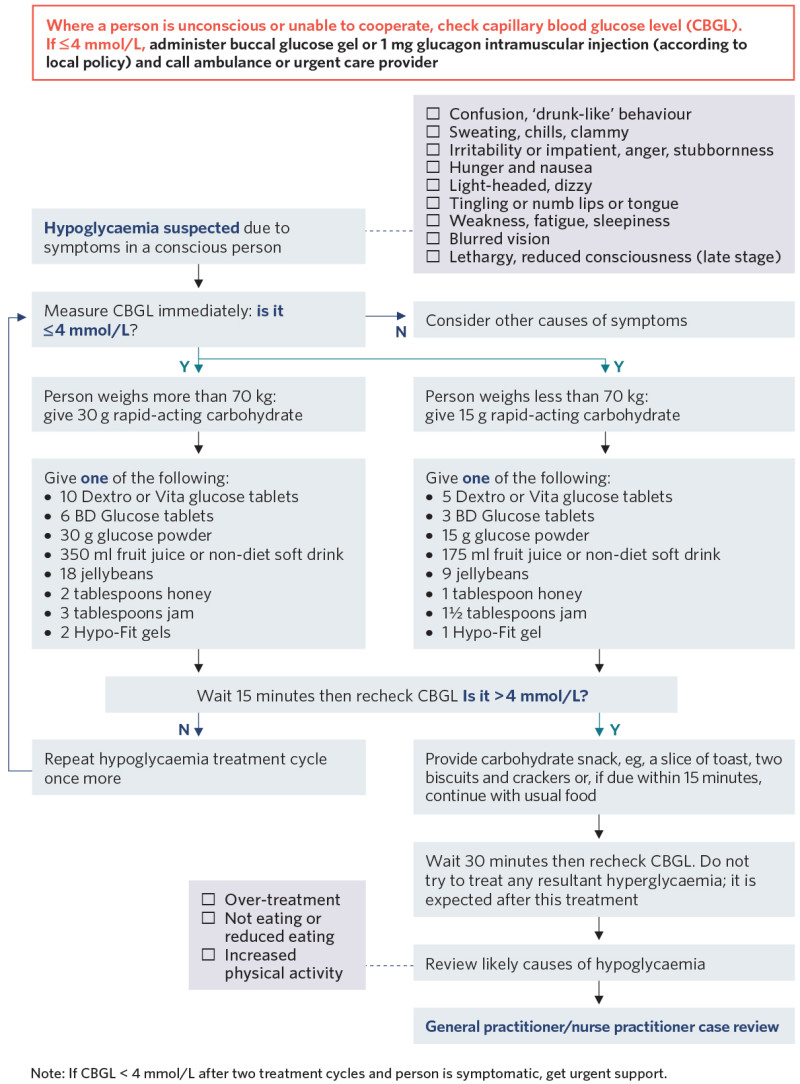

Hypoglycaemia (CBGL 4 mmol/L or less)

Hypoglycaemia happens in minutes to hours and needs a rapid response. It can present as confusion, dizziness, weakness and/or visual disturbances, rather than the more common tremors, sweating and ‘drunk-like’ confusion.

Note: Be aware that people with lifetime diabetes who have experienced multiple hypoglycaemic episodes can get hypo-unawareness. Here, the person gets few symptoms until BGL is very low (eg, 1.5–2 mmol/L) and consciousness changes.

Hypoglycaemia decision support (New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes 2022a)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

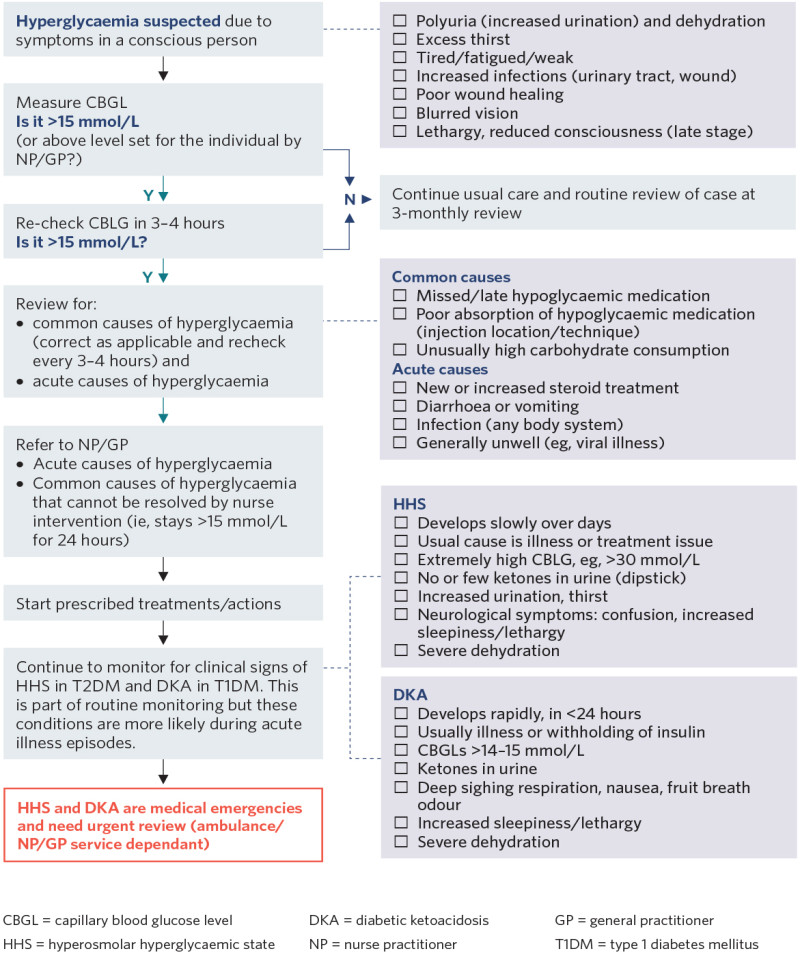

Hyperglycaemia

For frail older adults, a before-breakfast CBGL of approximately 8–10 mmol/L is generally acceptable provided they are not experiencing symptoms (bpacnz 2019).

Hyperglycaemia decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Sick day advice (New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes 2022b)

T1DM

Do not withhold basal insulin from people with T1DM, as this can result in diabetic ketoacidosis. Liaise with GP, NP or diabetes service for sick day advice.

T2DM

(Health Hawke's Bay 2023; New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes 2022b)

Acute illness (colds, infection, diarrhoea, vomiting) usually causes hyperglycaemia, but reduced oral intake may lead to hypoglycaemia.

Increase CBGL monitoring (three to four times a day).

- Expect CBGL to be between 8 and 15 mmol/L when sick.

- If CBGL stays above 15 mmol/L for 24 hours, refer to GP or NP.

- If CBGL is less than 8 mmol/L, give fruit juice or full-sugar fizzy drinks.

- If CBGL is higher than 8 mmol/L, give water or low-carbohydrate fluid to drink.

Maintain food and fluid intake.

- Chart food and fluid intake.

- Provide one glass of fluid per hour. Aim for about 1,500 mL in 24 hours.

- Provide usual food if person able to tolerate. If unable to tolerate, consider custard, jelly, yoghurt, ice cream (if diarrhoea, avoid dairy) and use soup, bread, Marmite/Oxo broth.

General advice is to give usual diabetes tablets or insulin during sick days except:

- do not give the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) empagliflozin

- do not give metformin or acarbose if person has diarrhoea or vomiting

- you may need to withhold sulfonylureas if person is not eating

- you may need to reduce basal or premixed insulin (by 20–30 percent) if person is not eating.

Contact GP or NP:

- to investigate cause of acute illness

- if in doubt about administering DM medications

- if diarrhoea or vomiting lasts more than 12 hours

- if CBGL stays above 15 mmol/L for 24 hours.

Treatment

T1DM

People with T1DM need basal insulin every day to avoid diabetic ketoacidosis. Engaging older people with T1DM with a diabetes service is recommended.

T2DM

Non-pharmacological

- Physical activity helps reduce blood sugar and is an effective frailty intervention. Culturally appropriate activities may be more appealing to kaumātua.

- A balanced diet including traditional cultural foods without undue restrictions is recommended. Full-fat products are recommended for people struggling to maintain weight.

- Weight loss is not recommended in frail older adults.

Pharmacological

DM pharmacological management escalates through a series of steps. Below is a brief overview of medication considerations. For more details, see the websites of the New Zealand Formulary and the New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes.

First-line medication

- Metformin: Diarrhoea is a common adverse drug effect (ADE), and the dose requires adjustment in the presence of renal impairment.

Second-line medication

- SGLT2i: Empagliflozin comes combined with metformin or as a separate tablet. Common ADEs include polyuria, skin reactions, urinary tract infection or urogenital infection (thrush). Rare ADEs include diabetic ketoacidosis (CBGLs may be normal) and necrotising fasciitis of the perineum. In practice, genital hygiene, including refreshing pads, is important.

- Long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists: Give dulaglutide or liraglutide as a weekly injection. ADEs include reduced appetite, nausea, diarrhoea or constipation and, less commonly, vomiting. Rare ADEs are myalgia, muscle weakness, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and thrombocytopenia.

- Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor: Vildagliptin comes either combined with metformin or as a separate tablet. Rare ADEs are angioedema when also taking angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and liver dysfunction (test before treatment and every 3 months in first year of treatment). Do not use with GLP-1 receptor blockers.

Third-line medication

- Thiazolidinedione: Pioglitazone increases the risk of heart failure and bone fractures.

- Sulfonylureas may be gliclazide or glipizide or glibenclamide. A common ADE is hypoglycaemia, especially if the person is not eating.

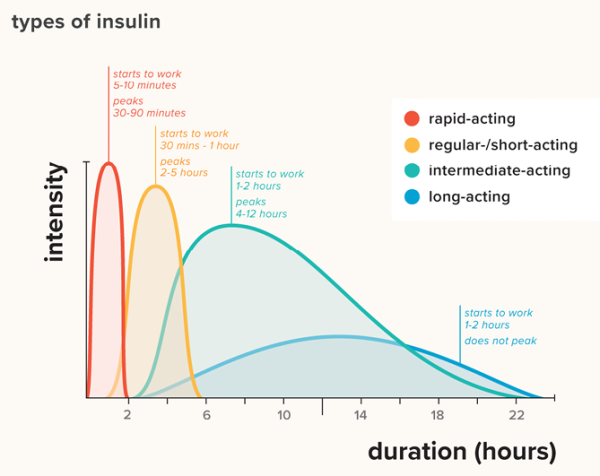

- Insulin is required in later stages of T2DM. It comes as short-, intermediate- or long- acting medication. Introduce it in steps based on its effectiveness (Ministry of Health 2022; New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes 2022a):

1. basal insulin (intermediate or long acting)

2. add a separate bolus (short-acting) insulin with largest meal or mixed insulin (short and long acting) with largest meal or, if the person has multiple similar- sized meals in a day, split the dose

3. insulin bolus with meals.

Source: Healthline https://www.healthline.com/health/type-2-diabetes/insulin-chart

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Care planning: monitoring

DM affects multiple systems of the body. Routine monitoring is an important part of the care plan. Appropriate target ranges for parameters are a balance between best outcome for DM and quality of life in frailty.

Blood pressure targets (Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee 2018)

- Systolic blood pressure target is < 140–150 mmHg.

- Avoid < 130 mmHg, which has been associated with falls in frail older adults.

Dyslipidaemia (bpacnz 2021)

In people with frailty and less than 5-year life expectancy, treating dyslipidaemia is unlikely to be beneficial.

Kidney disease

In annual review of glomerular filtration (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min is an indicator of disease), liaise with GP or NP for medication review.

Foot care (bpacnz 2021)

- Provide good-fitting shoes and skin care (use moisturiser) and keep nails short. Conduct neurovascular examination of feet each year. Refer to care via specialist service for older adults with high-risk feet. For new foot wound or infection, contact GP or NP urgently.

- For the New Zealand diabetes foot screening tool from Health New Zealand, go to: https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/For-the-health-sector/Health-sector-guidance/Diseases-and-conditions/Diabetes/diabetes-foot-screening-risk-stratification-tool.docx

References | Ngā tohutoro

bpacnz. 2019. Dialling back treatment intensity for older people with type 2 diabetes. URL: bpac.org.nz/2019/docs/diabetes-elderly.pdf.

bpacnz. 2021. The annual diabetes review: screening monitoring and managing complications. URL: bpac.org.nz/2021/diabetes-review.aspx.

Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. 2018. Diabetes in older people. Canadian Journal of Diabetes 42(Suppl 1): S283–95.

Health Hawke's Bay. 2023. Diabetes Care for Age Related Residential Care Facilities in Hawke’s Bay (revised edn). URL: healthhb.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Diabetes-Care-for-Age-Related-Residential-Care-Facilities-in-Hawkes-Bay-2023-v2.pdf.

Ministry of Health. 2022. Diabetes-related conditions. Revised URL: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/for-the-health-sector/health-sector-guidance/diseases-and-conditions/long-term-conditions/diabetes/about-diabetes/related-conditions/.

Mullane T, Harwood M, Warbrick I, et al. 2022. Understanding the workforce that supports Māori and Pacific peoples with type 2 diabetes to achieve better health outcomes. BMC Health Services Research 22(672): 1–8. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-022-08057-4.

New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes. 2022a. Type 2 diabetes management guidelines: Insulin. URL: t2dm.nzssd.org.nz/Subject-22-Insulin.

New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes. 2022b. Type 2 diabetes management guidelines: Sick day management in patients with diabetes. URL: t2dm.nzssd.org.nz/Section-95-Sick-day-management-in-patients-with-diabetes.

New Zealand Formulary. 2022a. Diabetes mellitus. URL: nzf.org.nz/nzf_3624?searchterm=diabetes.

New Zealand Formulary. 2022b. Insulins. URL: nzf.org.nz/nzf_3629.

Tane T, Selak V, Hawkins K, et al. 2021. Māori and Pacific peoples’ experiences of a Māori-led diabetes programme. New Zealand Medical Journal (Online) 134(1543): 79-89. PMID: 34695079.

Te Whatu Ora. 2023. Key findings from the 2021 Diabetes Virtual Register. URL: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/our-health-system/data-and-statistics/virtual-diabetes-tool/#key-findings-from-the-2021-virtual-diabetes-register.

Yu D, Zhao Z, Osuagwu UL, et al. 2021. Ethnic differences in mortality and hospital admission rates between Māori, Pacific, and European New Zealanders with type 2 diabetes between 1994 and 2018: a retrospective, population-based, longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet 9(2): e209–e217. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30412-5.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.