Dementia overview | Tirohanga whānui o te mate wareware (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Care planning

- Further resources

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe the impaired ability to think that is different from a usual consequence of ageing (Alzheimers New Zealand nd; Vuong et al 2019). It results in both cognitive and functional limitations. Dementia affects memory, orientation, comprehension and calculation. It compromises a person’s judgement as well as their ability to understand written and verbal language and to communicate. These limitations eventually result in a lack of mental capacity.

Key points

- Dementia is a progressive terminal illness (Mitchell et al 2009).

- The experience of dementia is different for everyone. Progression is variable, and what a person can do changes day to day (Alzheimers New Zealand nd).

- Both the person living with dementia and their loved ones go through numerous losses related to the disease process. It is important to consider the person and their whānau/family when providing care.

- To meet goals of care, the care team, whānau/family need to regularly review the progression of dementia (Mitchell et al 2009; Murray et al 2005).

Why this is important

People living with dementia experience a broad range of symptoms related to their disease. Understanding the disease process can help the health team adapt their approach to best support the person and their whānau/family.

Implications for kaumātua*

Research on dementia in Māori is very limited. However, the evidence available indicates that dementia presents up to 10 years earlier in Māori compared with New Zealand Europeans and that Māori have an increased risk of dementia because they have a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors (Cullum et al 2020).

Māori may interpret mate wareware (dementia) in a way that is different from a western medical view. Whānau/family may interpret the causes ‘within historical, cultural and social contexts rather than as physical illness or disease’ (Dudley et al 2019). In some instances, they may interpret it as part of a spiritual journey on which kaumātua are preparing to join their tīpuna (ancestors) and a normal part of growing old rather than a disease or illness (Dudley et al 2019). It is important to consider and support these viewpoints when providing holistic care.

Research (Dudley et al 2019) found factors that can have a positive impact on those with mate wareware are:

- using te reo Māori (which may have been the first language of the kaumātua but they were suppressed from using it as a child)

- participating in cultural activities and events that are seen as rongoā (medicine) to slow or prevent progression of the disease

- maintaining kaumātua independence and involving them in activities for as long as possible.

While kaumātua with dementia may live in aged residential care, it is still important to give their whānau/family all of the information, knowledge and resources they need to best support their ongoing involvement in the care of their loved ones.

Assessment

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a comprehensive clinical assessment by a general practitioner, nurse practitioner, geriatrician or old-age psychiatrist. To have a diagnosis of dementia, the person must have a history of significant cognitive decline (attention, planning, inhibition, learning, memory, language, visual perception, spatial skills or social skills) that interferes with independence in everyday activities (Hugo and Ganguli 2014).

Common observable deficits include:

- attention – finding it difficult to focus in environments that contain multiple stimuli (eg, TV, radio and conversation)

- executive function – being unable to perform previously familiar tasks, needing help with day-to-day decisions, loss of initiative and poor judgement

- learning and memory – struggling to recall, being repetitive in conversation and behaviour, needing reminders to complete task (eg, eating) and being confused about time and place

- language expression and comprehension – using terms such as ‘that thing’ and ‘you know what I mean’, and sometimes failing to recall names of close friends and family

- social skills – being insensitive to social standards with little insight and so becoming socially withdrawn or isolated

-

motor and visual function – losing ability to use tools, write or do other previously familiar activities (eg, knitting) and getting lost.

Dementia types

Common types of dementia (Hugo and Ganguli 2014)

Alzheimer's disease

Symptoms

Early stage – memory loss, difficulty finding words, poor judgement; later stages often include behaviours that challenge, irritability, agitation, wandering, gait disturbances, dysphagia, incontinence

Pathology

Progressive loss of synapses and neurons, and accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles

Vascular dementia

Symptoms

History of stroke or transient ischaemic attacks (TIA), poor attention and executive function, gait disturbance, incontinence, personality changes

Pathology

Cerebrovascular disease (‘white matter changes’), often a stepwise progression but can be rapid

Mixed dementia

Most commonly, a combination of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia

Fronto-temporal lobe

Symptoms

Personality and behaviour change (eg, withdrawal, loss of interest in activities, poor personal hygiene, social disinhibition). Can include a loss of speech and empathy and rigid behaviours

Pathology

Atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Gradual progression, early-onset dementia

Dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease

Symptoms

Impaired attention, visuospatial awareness and executive functioning, hallucinations, delusions and depression. Repeated falls and syncope, loss of consciousness (resolves), poor autonomic regulation (vital sign fluctuation, sweating, impaired peristalsis)

Pathology

Presence of Lewy bodies in brain, progression is gradual. In dementia with Lewy bodies, cognitive impairment appears before movement disorder

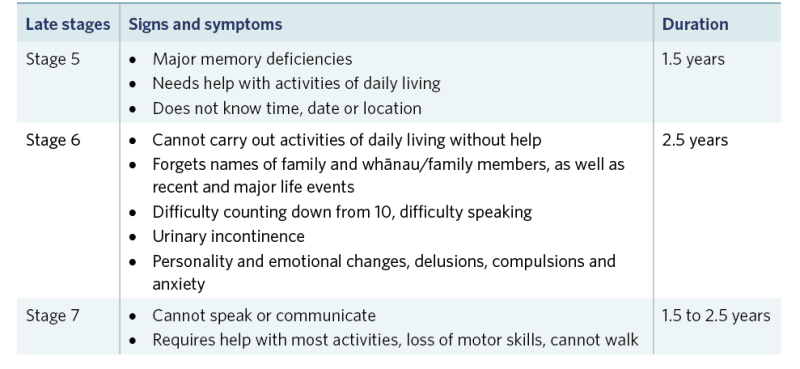

Staging

Global Deterioration Scale/Reisberg Scale (abbreviated) (Dementia Care Central 2020)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Treatment

Supporting someone living with dementia should include meeting their basic needs such as maintaining nutrition and hydration and managing activities of daily living. Engaging the person in meaningful activity and supporting them to maintain as much independence as possible are key to their quality of life. Currently dementia has no cure. However, some medications can slow the progression of the disease.

Reaching a prognosis is particularly difficult, and most tools are no more effective than clinical judgement. However, one study found that pneumonia, febrile episodes and eating problems were common in the last 3 months of life (Mitchell et al 2009).

Care planning

Person-centred care (Fazio et al 2018)

Person-centred care, a term first used by Kitwood (Kitwood and Bredin 1992; Fazio et al 2018), remains the best-supported and most well-researched approach to care for people with dementia. The following are key themes of this approach.

- The person living with dementia is more than a diagnosis. Get to know them and support them to uphold their values, beliefs, interests, abilities, likes and dislikes.

- It is important to see the world from the perspective of the person living with dementia. Recognise and accept their behaviour as a form of communication. Validating their feelings can help the person connect with their reality.

- Every experience or interaction is an opportunity for meaningful engagement. This should support their interests and preferences and allow for their choice (eg, of foods, music, clothes, activities). Remember all people with dementia can experience joy, comfort and meaning in life.

- Build and nurture authentic, caring relationships that demonstrate respect and dignity. Focus on the interaction when completing tasks. Supportive relationships are about ‘doing with’ rather than ‘doing for’.

- Create a supportive community that allows for comfort and celebrates success and occasions.

Whānau/family care

The person living with dementia may be unable to plan for the future. It is important to ensure whānau/families have an understanding of the clinical progression of dementia so they can help plan for future care needs, including end-of-life care.

Further resources

Dementia STARs education series www.nzdementia.org/Dementia-STARs.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Alzheimers New Zealand. nd. What is dementia? URL: alzheimers.org.nz/about-dementia/what-is-dementia.

Cullum S, Dudley M, Kerse N. 2020. The case for a bicultural dementia prevalence study in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal 133(1524): 119–25. URL: journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/the-case-for-a-bicultural-dementia-prevalence-study-in-aotearoa-new-zealand.

Dementia Care Central. 2020. Stages of Alzheimer’s and dementia: durations and scales used to measure progression (GDS, FAST and CDR). URL: www.dementiacarecentral.com/aboutdementia/facts/stages.

Dudley M, Menzies O, Elder H, et al. 2019. Mate wareware: understanding ‘dementia’ from a Māori perspective. New Zealand Medical Journal 132(1503): 66–74. URL: journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/mate-wareware-understanding-dementia-from-a-maori-perspective.

Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, et al. 2018. The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist 58(Suppl 1): S10–S19. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnx122.

Hugo J, Ganguli M. 2014. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 30(3): 421–42. DOI: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.001.

Kitwood T, Bredin K. 1992 Towards a theory of dementia care: personhood and well-being. Ageing and Society 12: 269–87.

Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. 2009. The clinical course of advanced dementia. New England Journal of Medicine 361(16): 1529–38. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234.

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. 2005. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 330(7498): 1007–11. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007.

Vuong JT, Jacob SA, Alexander KM, et al. 2019. Mortality from heart failure and dementia in the United States: CDC WONDER 1999–2016. Journal of Cardiac Failure 25(2): 125–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.11.012.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.