To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Care planning

- Delirium prevention resource

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023

Definition

Delirium (also known as acute confusion) is a psychiatric syndrome characterised by a change in the person’s ability to pay attention, level of consciousness and cognitive function. It has a sudden onset (over 1–2 days) and fluctuating course, with the person experiencing periods of hyperactivity, hypoactivity and normal function over a 24-hour period (Jeong et al 2020; Ramírez Echeverría et al 2022; Wilson et al 2020).

Key points

- Delirium is not always easy to recognise, and so the experience can be distressing for older people, their whānau/family and those caring for them.

- It may not be possible to identify the underlying cause of delirium.

- Hyperactive delirium can be confused with behaviours that challenge in people living with dementia.

- Hypoactive delirium results in quiet people and so may go unnoticed.

- In any behaviour change (hypoactivity or hyperactivity), the safest approach is to assume delirium first and follow up other issues after that (Nitchingham and Caplan 2021).

- Minimising the risk of delirium can have a significant impact on quality of life (Aung Thein et al 2020).

Why this is important

Delirium in older people is a medical emergency that needs immediate referral and treatment. People with delirium have a higher mortality rate than those without delirium (Jeong et al 2020).

Traditionally, delirium was considered reversible. However, recent evidence suggests that delirium may become chronic and can cause irreversible decline in cognitive and physical function (Whitby et al 2022). Chronic delirium occurs most commonly in people who have their diagnosis and treatment of delirium delayed, have moderate to severe frailty and have multiple chronic conditions, and in people with cognitive impairment.

Implications for kaumātua*

Kaumātua and/or their whānau/family may have a different interpretation of delirium and consider that it may not have a physical cause. This is closely related to the holistic view of health from a Māori perspective (Ministry of Health 2017). A disruption or disturbance in one dimension of a person’s health affects the other dimensions.

From a Māori perspective, the behaviours observed in both hyperactive and hypoactive delirium may be due to a disturbance in the person’s wairua (spirituality) or a breach of their personal tapu (see the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information). It is important to acknowledge this cultural perspective and include holistic interventions when considering treatment of delirium.

Kaumātua and whānau/family may place equal importance on addressing wairua disturbance as treating physiological causes of delirium. For accuracy, wairua disturbances should only be interpreted from a Māori world view. In this situation, listening to kaumātua, whānau/family and other sources of cultural knowledge will be vital.

Complementary, culturally informed interventions to address wairua disturbance may include karakia (prayer), pure (cleansing rituals) and/or whakanoa (ritual that lifts or removes tapu).

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Everyone living in aged residential care should be considered at risk of developing delirium if they become acutely ill. A sudden change in mental status should always initiate an assessment for delirium. Worsening motor function is an important diagnostic clue for delirium, especially in people living with dementia. Using a tool to support delirium diagnosis is recommended (Morandi et al 2019).

Note: If some health providers, whānau/family or friends report witnessing confusion while others do not, the safest approach is to assume this is fluctuating delirium until proven otherwise.

Delirium assessment tools

RADAR: Recognising delirium as part of your routine

Authors suggest routine use of the RADAR tool (Morandi et al 2019; Voyer et al 2015).

When you gave the patient their medication:

- was the patient drowsy?

- did the patient have trouble following your instructions?

- were the patient’s movements slowed down?

The patient is considered positive for delirium when the assessor answers ‘Yes’ to at least one question.

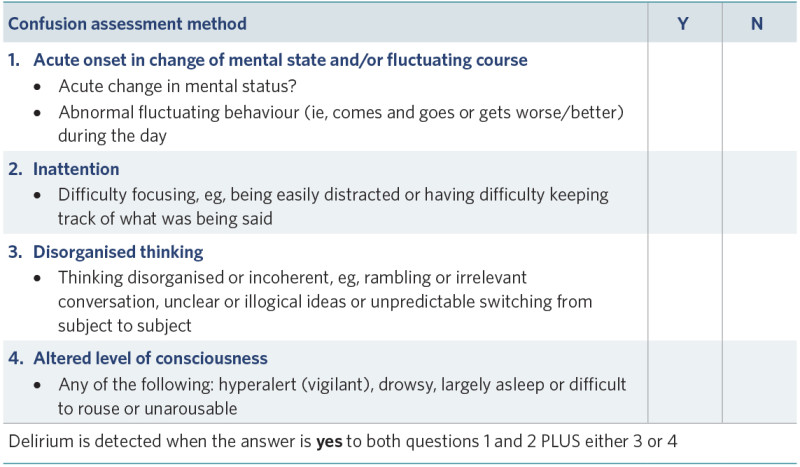

Confusion assessment method (Inouye et al 1990)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

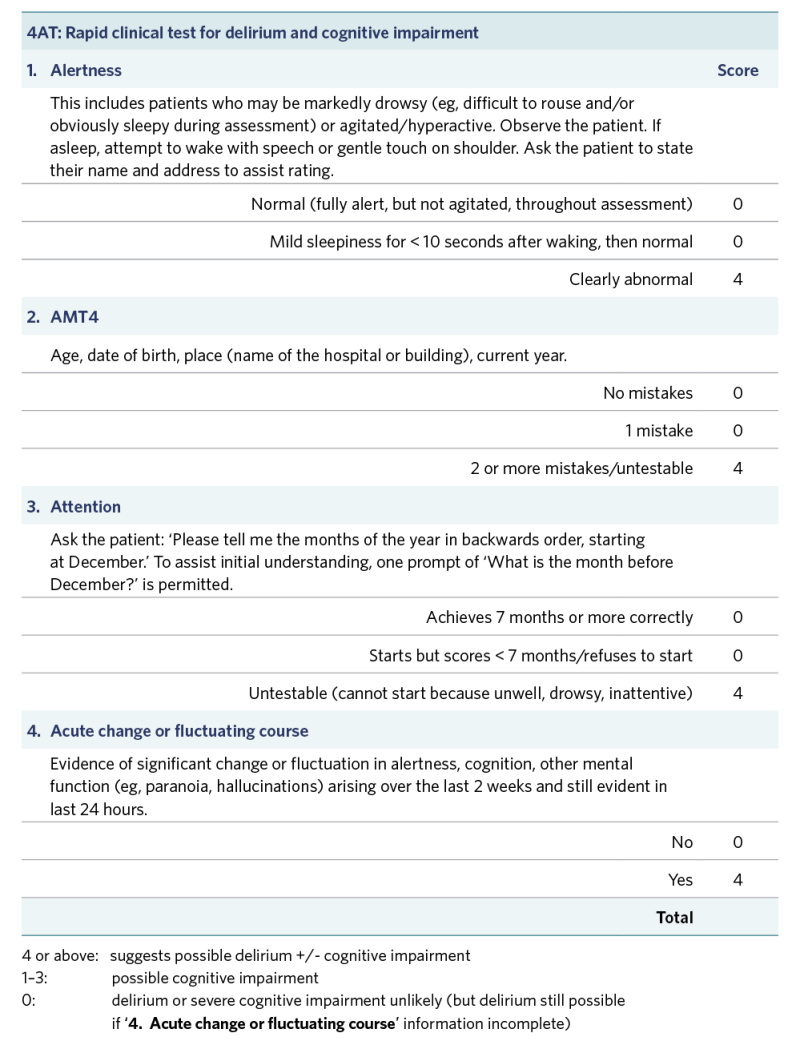

The 4AT

This is a quick (< 2 minutes) validated screening tool. It measures: Alertness, Abbreviated Mental Test, Attention and Acute change or fluctuating course (www.the4at.com).

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Treatment

Prevention

The best ‘treatment’ for delirium is prevention – that is, implementing strategies that reduce the likelihood that the person will experience delirium. While this is ongoing best practice, it is particularly important to do when someone becomes acutely ill.

A tool called ‘PINCHES ME kindly’ sets out the nine aspects to address to prevent delirium in older people (Gee et al 2016). The acronym stands for: Pain, Infection, Nutrition, Constipation, Hydration, Exercise, Sleep, Medication and Environment.

Treatment

In all cases, diagnosing and treating the underlying cause of delirium (eg, infection, dehydration, adverse effect of medication) is fundamental to potentially reversing symptoms of delirium.

In addition, the delirium syndrome itself needs care and treatment.

- Non-pharmacological approaches are considered best practice. You should try them first and continue to use them even if medication for delirium symptoms is prescribed.

- Pharmacological treatment of delirium includes the use of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines. Medication is reserved for psychiatric symptoms that cause the person distress (eg, hallucination and delusions), and it is used for the shortest possible time (Morandi et al 2019).

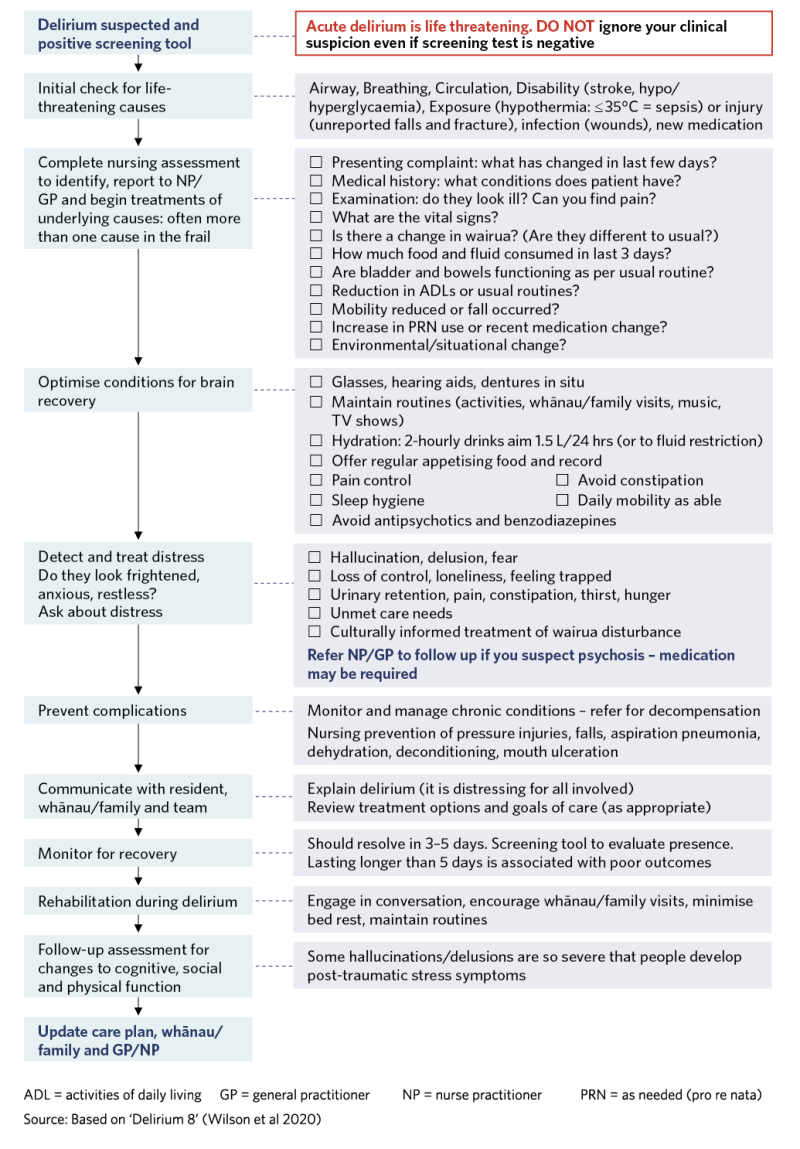

Care planning

Because individuals differ in their experiences of delirium, care planning needs to be individualised and responsive to the older person’s needs. The decision-support flowchart on the following page provides a generic approach that can be adapted to an individual’s requirements.

Delirium prevention resource

Think Delirium prevention project – PINCHES ME kindly Canterbury District Health Board (Gee et al 2016)

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Aung Thein MZ, Pereira JV, Nitchingham A, et al. 2020. A call to action for delirium research: meta- analysis and regression of delirium associated mortality. BMC Geriatrics 20(1): 325. DOI: 10.1186/s12877- 020-01723-4.

Gee S, Bergman J, Hawkes T, et al. 2016. Think delirium: Preventing delirium amongst older people in our care. Tips and strategies from the Older Persons’ Mental Health Think Delirium Prevention project. Christchurch: Canterbury District Health Board. URL: www.researchgate.net/publication/303876489_THINK_delirium_Preventing_delirium_among_older_people_in_

our_care_Tips_and_strategies_from_the_Older_Persons%27_Mental_Health_Think_Delirium_Prevention_project.

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. 1990. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine 113(12): 941–8.

Jeong E, Park J, Chang SO. 2020. Development and evaluation of clinical practice guideline for delirium in long-term care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(21). DOI: 10.3390/ ijerph17218255.

Ministry of Health. 2017. Māori health models – Te Whare Tapa Whā. URL: www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/maori-health-models/maori-health-models-te-whare-tapa-wha.

Morandi A, Pozzi C, Milisen K, et al. 2019. An interdisciplinary statement of scientific societies for the advancement of delirium care across Europe (EDA, EANS, EUGMS, COTEC, IPTOP/WCPT). BMC Geriatrics 19(1): 253. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-019-1264-2.

Nitchingham A, Caplan GA. 2021. Current challenges in the recognition and management of delirium superimposed on dementia. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 17: 1341–52. DOI: 10.2147/NDT. S247957.

Ramírez Echeverría MdL, Schoo C, Paul M. 2022. Delirium. In StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Voyer P, Champoux N, Desrosiers J, et al. 2015. Recognizing acute delirium as part of your routine [RADAR]: a validation study. BMC Nursing 14: 19. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-015-0070-1.

Whitby J, Nitchingham A, Caplan G, et al. 2022. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv. DOI: 10.1101/2022.01.20.22269044.

Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C, et al. 2020. Delirium. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 6(1): 90. DOI: 10.1038/s41572-020-00223-4.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.