Care during the last days of life | Pairuri (palliative care) (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Care planning

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

- Appendix

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Last days of life are the hours or days during which death is imminent. Te Ara Whakapiri: Principles and guidance for the last days of life and its toolkit offer a guide to care at this time in New Zealand (Ministry of Health 2017).

Why this is important

People require health care from conception to interment (when they reach their final resting place after death). The quality of care during the last hours and days of life directly impacts on the dying person. Just as importantly, the way death and dying is managed impacts the experience of grief for all those left behind (Detering et al 2021).

Implications for kaumātua*

Underpinned by Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie 1985), Te Ara Whakapiri takes a holistic approach to promoting the wellbeing of the person and their whānau/family as the end of life nears. From te ao Māori (Māori world view) the last days of life is believed to be the time when the person’s wairua (spirit) moves across the ārai (veil) from the physical to the metaphysical realm (Nelson-Becker and Moeke-Maxwell 2020). This is considered a critical aspect of the life phase (Moeke-Maxwell et al 2014).

The individual and cultural preferences for Māori during the last days of life are diverse. It is ‘essential that care administered at end of life is inclusive of their whānau/family and is culturally informed, relevant, and well-supported by health professionals’ (Moeke-Maxwell et al 2019). For this reason, health professionals must create space for discussion with whānau/family about the last days of life both before the end of life and during the dying process. They should document preferences in the plan of care.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Tikanga

Because the needs of whānau/family will vary, it is best to allow them to lead. The following are some tikanga (Māori cultural customs/traditions) that whānau/family may choose to observe (see the Guide for health professionals caring for kaumātua | Kupu arataki mō te manaaki kaumātua for more information).

- Gathering together with waiata (songs) and karakia (prayers/incantations) is a common way in which whānau/family express aroha (love, compassion, empathy) at this time.

- Someone stays with the dying person or tūpāpaku (deceased) at all times.

- People cannot take food or drink into the room of the dying person or tūpāpaku. Doing so breaches the separation and balance of tapu (sacred, restricted, prohibited) and noa (ordinary, neutral, unrestricted).

-

After the person’s death, it is common for mourners to lift the tapu and restore noa by sprinkling themselves with wai (water). Have a bowl of wai available outside the room containing the tūpāpaku so that manuhiri (visitors) can bless themselves after leaving the deceased person’s space.

- After the person’s death, there will be a time when the wairua must settle. Whānau/family will generally have intuition about when this has happened. After this time, they may wish to wash, prepare and dress their loved one.

After the person’s death, the whānau/family may wish to lift the tapu of the room or space where their loved one lived. This process is called a takahi. A leader will say karakia while sprinkling the room or area with wai.

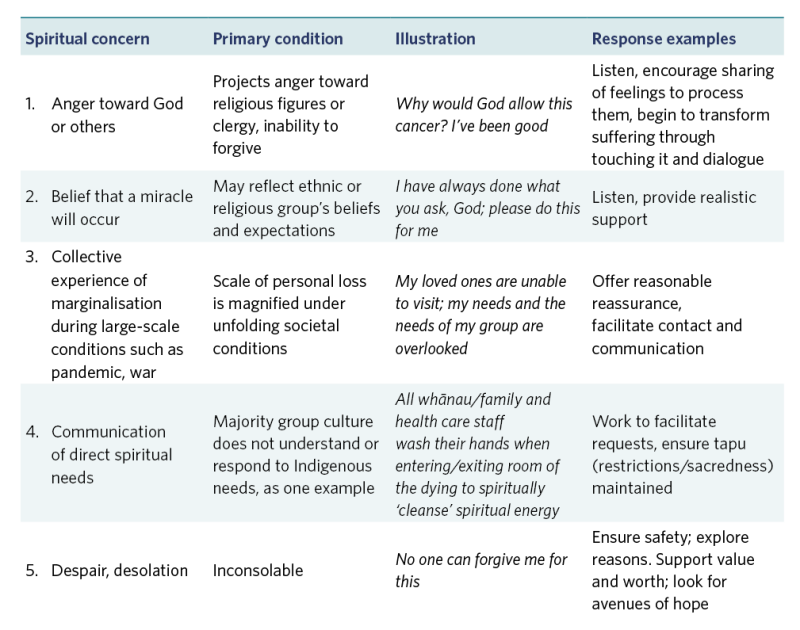

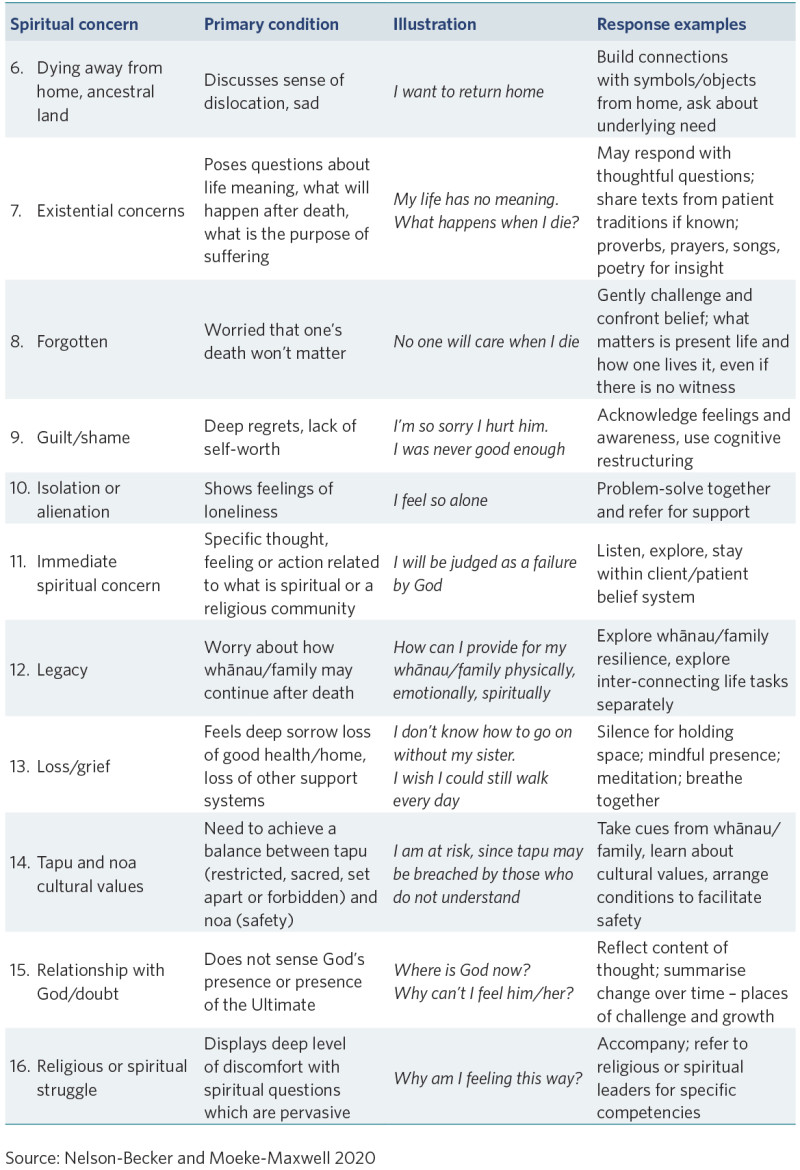

Spiritual concerns

Kaumātua may experience spiritual distress in the last days of life. Nelson-Becker and Moeke-Maxwell (2020) provide a helpful table of examples and useful responses (see the appendix of this guide).

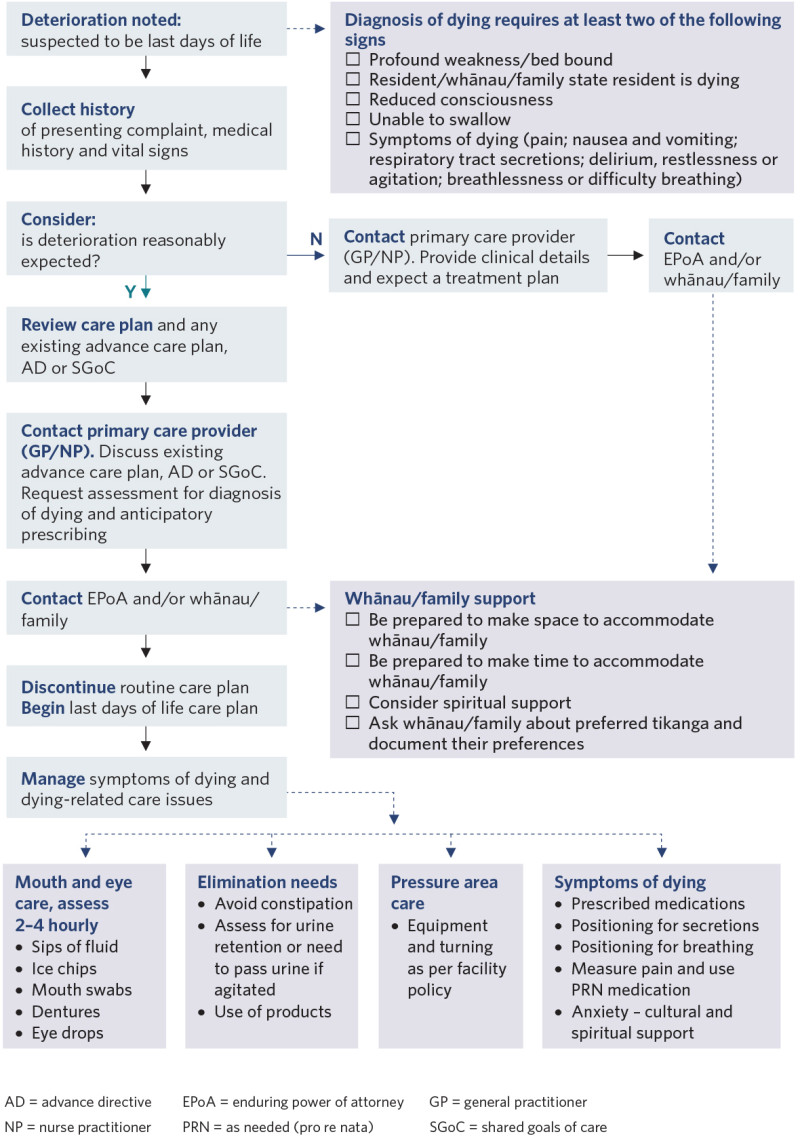

Assessment

The diagnosis of dying is made only after a clinical assessment confirms that the presenting situation is not reversible. An irreversible situation may be absolute (eg, end-stage disease) or it may occur because the older person is unwilling to consent to treatments (eg, deciding against hospitalisation or invasive treatments). In aged residential care, a registered nurse often completes the first assessment and refers to the primary care provider (general practitioner or nurse practitioner) for support with the diagnosis and management plan.

Care planning

Care focuses on managing the physical and holistic symptoms associated with the dying process, such as the following.

Physical care may involve:

- medication management – making changes to the plan and using anticipatory prescribing

- responding to the common symptoms of dying:

- pain

- nausea and vomiting

- respiratory tract secretions

- delirium, restlessness or agitation

- breathlessness or difficulty breathing

- continuing care – responding to mouth care, pressure area care and elimination needs

- environmental management (temperature, noise).

Holistic care may involve:

- guiding loved ones through the dying process

- acknowledging the emotional impact on whānau/family and loved ones

- providing space for gathering

- continuing to provide wairua or spiritual support throughout the process

- accepting the expression of grief in whatever form it takes.

Decision support

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Detering KM, Sinclair C, Buck K, et al. 2021. Organisational and advance care planning program characteristics associated with advance care directive completion: a prospective multicentre cross- sectional audit among health and residential aged care services caring for older Australians. BMC Health Services Research 21: 700. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-021-06523-z.

Durie MH. 1985. A Māori perspective of health. Social Science Medicine 20(5): 483–6.

Ministry of Health. 2017. Te Ara Whakapiri: Principles and guidance for the last days of life. Wellington: Ministry of Health. URL: www.health.govt.nz/publication/te-ara-whakapiri-principles-and-guidance- last-days-life.

Moeke-Maxwell T, Mason K, Toohey F, et al. 2019. Pou aroha: an Indigenous perspective of Māori palliative care, Aotearoa New Zealand. In: R MacLeod, L Van den Block (eds), Textbook of Palliative Care. Cham: Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-77740-5_121.

Moeke-Maxwell T, Nikora LW, Te Awekotuku N. 2014. End-of-life care and Māori whānau resilience. MAI Journal 3(2). URL: https://www.journal.mai.ac.nz/content/end-life-care-and-m%C4%81ori-wh%C4%81nau-resilience.

Nelson-Becker H, Moeke-Maxwell T. 2020. Spiritual diversity, spiritual assessment, and Māori end-of-life perspectives: attaining Ka Ea. Religions 11(10): 536. DOI: 10.3390/rel11100536.

Appendix: Examples of spiritual distress and possible responses

View a higher resolution version of these images in the relevant guide.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.