Advance care planning | Te whakamahere tauwhiro whakamau (Frailty care guides 2023)

To return to the list of all of the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.

Contents

- Definition

- Why this is important

- Implications for kaumātua

- Assessment

- Care planning

- Decision support

- References | Ngā tohutoro

The information in this guide is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of June 2023.

Definition

Advance care planning is a process of discussion and shared planning for future health care that a competent person undertakes with their whānau/family (at the person’s discretion) and health care professionals (Health Quality & Safety Commission 2022). Advance care planning provides an opportunity for a person to develop and express preferences for future care based on:

- their values, beliefs, concerns, hopes and goals

- a better understanding of their current and likely future health

- the treatment and care options available.

Advance care planning is about shared decision-making and delivering care that is centred on the person (and their whānau/family) now and in the future, including at the end of life. It helps to prepare all involved for what may lie ahead and with making decisions in the future that align with what matters most to the person.

- Shared goals of care are the outcome of a decision-making process between the person, whānau/family (as appropriate) and clinical team. They may result from an advance care planning conversation or a stand-alone process. The aim is to set a direction for an episode of care, including any limitations in medical treatment such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and the level of treatment desired or available in likely clinical scenarios (Martin et al 2019).

- An advance directive (AD) is a consent to, or a refusal of, a specific treatment that may or may not be offered in the future. It may be written or oral. For the AD to be valid and legally binding, the person must, at the time of creating it, be competent, informed and acting freely and must anticipate that health professionals will use the AD later to direct the treatment they offer. An AD may only be used when the person lacks capacity. A person cannot use an AD to choose assisted dying.

- Advance treatment planning is a process of planning for likely future health needs. It is an important process for people who lack capacity. It is a clinician-led process that includes consulting pre-existing documents and the person’s representatives.

Key points

- All of the above (advance care planning, shared goals of care, AD and advance treatment planning) involve having conversations with the aim of giving the person care and treatment that are consistent with their values, beliefs and clinical needs. Having the conversation is more important than which form is used to capture it.

- People with capacity (competence):

- choose who to include in conversations

- decide on their (clinically appropriate and reasonable) care and treatment options

- should be encouraged to document their preferences.

- The following conditions apply to people who lack capacity (as established through a formal capacity assessment).

- Health professionals have a legal obligation to consider the resident’s expressed preferences when determining which treatments to offer. If there is a valid AD that relates to that specific treatment, it is legally binding.

- Health professionals should make every attempt to include the person’s representatives (enduring power of attorney: personal care and welfare) in treatment planning. Note: The attorney cannot ‘refuse any standard medical treatment or procedure intended to save that person’s life or to prevent serious damage to that person’s health’ (Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988). For example, they cannot refuse CPR on behalf of the resident (New Zealand Government 2021).

- All of the above processes inform decision-making. They do not replace clinical judgement or accountability for decisions about what treatment to offer. For example, health professionals may judge CPR to be clinically inappropriate (unlikely to save the life of a person with advanced frailty) and so make a ‘do not resuscitate’ decision.

- An advance treatment plan is the outcome of reviewing decisions the person made when they had capacity, talking with the person’s representative(s) and applying clinical judgement.

Why this is important

Understanding the values, goals and wishes of the person living in care helps the health care team make decisions that are most likely to uphold the mana (dignity, status, esteem) of the person.

Implications for kaumātua*

Given the basis for advance care planning is to honour the values and wishes of the individual and their whānau/family, it is important to involve all the necessary people and make sufficient time and space available for these conversations to happen. Providing support and guidance to the whānau/family throughout the process is also vital.

The whānau/family members involved may extend to a much wider group of people than those typically considered immediate ‘next of kin’. The method of communication with whānau/family should also be flexible – for example, kanohi ki te kanohi (face to face) meetings, email, telephone or video conferencing. The whānau/family involved in each case should determine the method based on their own preference.

*Kaumātua are individuals, and their connection with culture varies. This guide provides a starting point for a conversation about some key cultural concepts with kaumātua and their whānau/family. It is not an exhaustive list; nor does it apply to every person who identifies as Māori. It remains important to avoid assuming all concepts apply to everyone and to allow care to be person and whānau/family led.

Assessment

Conversations about choices to do with frailty and care or treatment occur when a person is admitted to aged residential care, at routine reassessments and after significant changes in their condition. Having a standard process helps these conversations to take place (Siu et al 2020). As a general guide, it is helpful to discuss five levels of treatment with the person and their whānau/family when deciding about shared goals of care and advance care planning.

-

Restorative (full) for CPR:

Treatment aims to preserve life and may require transfer to acute hospital for diagnostic procedures and treatments that are not available in aged residential care.

-

Restorative (conditional) not for CPR:

Treatment aims to preserve life or maintain the best possible health outcome. It may require assessment in urgent care, while limiting treatment to the options manageable and/or available in aged residential care.

-

Active care on-site not for CPR:

Treatment aims to slow decline and enhance quality of life. Generally, the guidance is not for hospital transfer. However, transfer to hospital may be necessary following advice from a general practitioner or nurse practitioner. Examples of such situations include traumatic injury (eg, suspected fracture) and acute surgical issues (eg, suspected bowel obstruction).

-

Comfort care on-site not for CPR:

Treatment aims to optimise comfort rather than to try to prolong life. This phase may be for a short or extended period.

- Care of dying: Treatment aims to provide comfort for the person living in care and their whānau/family in the last days or hours of life, when ‘dying’ has been diagnosed.

Key points

- Research suggests it is almost impossible to predict when dying will occur. The levels of assessment outlined above are an approach to care, not an approach to dying (Stow et al 2020).

- If a person experiences an acute illness, it is always necessary to complete a clinical assessment to determine whether it is possible to address the illness no matter what level of intervention the person has chosen.

- All treatments (eg, subcutaneous fluids and antibiotics) may be considered at all levels of intervention (except active dying) but may be stopped if the treatment does not reverse the underlying condition. Thorough communication with the older person (as able) and their whānau/family is essential if treatments are stopped on the reasoning that they are futile, regardless of what level of intervention is involved.

- When competent older people with frailty become unwell, their ability to make rational decisions can be compromised. When they lack this capacity temporarily, the health care team must make sound clinical judgements on their behalf.

Care planning

- Advance care planning www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-work/advance-care-planning/acp-information-for-clinicians

- Shared goals of care resources www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-work/advance-care-planning/talkingcovid/arc-specific-resources

Decision support

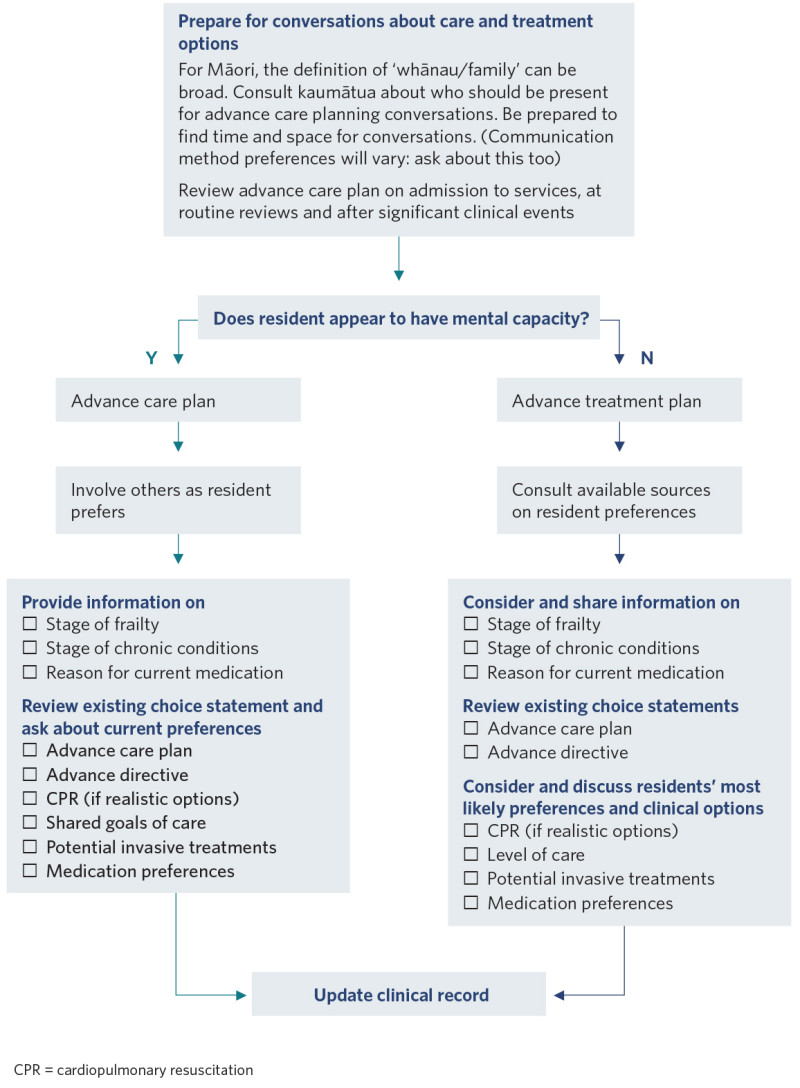

View a higher resolution version of this image in the relevant guide.

References | Ngā tohutoro

Health Quality & Safety Commission. 2022. Advance care planning. URL: www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-work/advance-care-planning.

Martin RS, Hayes BJ, Hutchinson A, et al. 2019. Introducing goals of patient care in residential aged care facilities to decrease hospitalization: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 20(10): 1318–24.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.017.

New Zealand Government. 2021. Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) for personal care and welfare. URL: www.govt.nz/browse/family-and-whanau/enduring-power-of-attorney-epa-for-personal-care-and-welfare.

Siu HYH, Elston D, Arora N, et al. 2020. A multicenter study to identify clinician barriers to participating in goals of care discussions in long-term care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 21(5): 647–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.022.

Stow D, Matthews FE, Hanratty B. 2020. Timing of GP end-of-life recognition in people aged >75 years: retrospective cohort study using data from primary healthcare records in England. British Journal of General Practice 70(701): e874–e879. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp20X713417.

If you have feedback about the Frailty care guides | Ngā aratohu maimoa hauwarea, click here.